Note: This article was written in the spring of 2009 and published in the final print issue of Filmbobbery (10:4).

As I am saying farewell with this issue, I thought it might be interesting to look at how some of our favorite film stars have also said farewell. Several have gone out in great style and fanfare while others have not been so lucky. Most of us never know in advance when we will be passing on, and so cannot plan a dignified, unforgettable exit. Even those who retire from the film industry don’t always have control over the quality of their final film appearances. Sean Connery, for example, hasn’t acted since he starred in (and served as executive producer for) the mostly wretched The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen in 2000. He declined to appear in last year’s Indiana Jones movie and has indicated that he will no longer act, no matter what is offered to him. That’s his prerogative, of course, but it’s a shame that his last film is such a dog. It is not a fitting farewell for him.

Most people would agree that Heath Ledger bowed out with an incredible turn as The Joker in last year’s The Dark Knight. I agree; however, it is not his final film appearance. That is yet to come, in Terry Gilliam’s fantasy The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, due later this year. Ledger’s untimely death threw the production into chaos and the bulk of his role is being filled by Johnny Depp, Jude Law and Colin Farrell. That movie will be Ledger’s actual swan song.

Fate often interrupts life at costly junctures; at least in terms of film careers. We’ll never know what cinematic treasures we have missed because of stars’ premature death or retirement. What would Ledger, James Dean, Greta Garbo, Grace Kelly, Charlie Chaplin, Brandon De Wilde, Marilyn Monroe or Brad Renfro accomplished given further opportunity? All we can do is mourn their loss and enjoy what they have left behind.

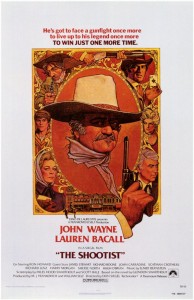

So who has gone out with the most style and substance? I always point to the Duke, for The Shootist (1976) is a valedictory film for him. It provides a perfect exclamation point to his career, being a western that, like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, is all about how the relentless march of civilization puts to an end rugged, self-determining individualism. It gives John Wayne the opportunity (as the fictional gunfighter John Bernard Books) to state his code of living, and to show by example how to face what is sure to be an unpleasant ending (from cancer; resonant because Wayne himself suffered from the disease at least twice, eventually dying from it).

Books’ ultimate choice regarding how he is to die is morally ambiguous, but he’s going out on his terms. Wayne couldn’t have chosen a better vehicle with which to depart the silver screen, where he had starred in over 100 films over almost half a century.

A couple of years after making The Shootist, however, Wayne was still itching to work, and he was in negotiations to play Gene Wilder’s sidekick in The Frisco Kid (1979), a supporting part which was eventually filled by Harrison Ford. Due to John Wayne’s salary demands and failing health, however, the deal was not consummated. While it would have been interesting to see Wayne playing straight man to Wilder’s unlikely Polish cowboy, I think it is a good thing that the deal fell through. Wayne’s final film serves as a tribute to an incredible career, and it is the way he should be remembered.

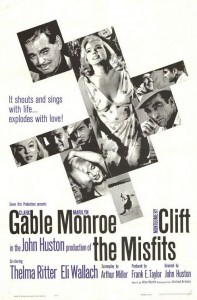

Clark Gable’s career was uneven at best after World War II but he could still rise to the occasion when the right script came along. Such was the case with The Misfits (1961), which also served as Marilyn Monroe’s cinematic swan song. The film is a little too literary for some viewers yet there is no denying Gable’s star power and acting ability as he portrays Gay Langland, a hard-driving cowboy now reduced to rounding up wild horses to sell for dog food. When he meets Marilyn Monroe, as divorcee Roslyn Taber, some of his old swagger returns.

Clark Gable’s career was uneven at best after World War II but he could still rise to the occasion when the right script came along. Such was the case with The Misfits (1961), which also served as Marilyn Monroe’s cinematic swan song. The film is a little too literary for some viewers yet there is no denying Gable’s star power and acting ability as he portrays Gay Langland, a hard-driving cowboy now reduced to rounding up wild horses to sell for dog food. When he meets Marilyn Monroe, as divorcee Roslyn Taber, some of his old swagger returns.

Filming in the hot Nevada desert was strenuous, and Gable suffered a heart attack immediately after filming wrapped, dying from another less than two weeks later. According to scriptwriter Arthur Miller, Gable saw the rough cut of the film before his heart attack and felt it was the best movie he had ever made, one which finally allowed him to actually “act.” Monroe is also good in the film, but not quite as impressive as Gable. She began to make one more film, Something’s Got to Give, but was fired during production and died from an accidental drug overdose soon afterward.

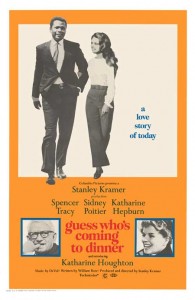

Another actor who died from a heart attack just after he finished his last film is Spencer Tracy, and the film is Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967). Groundbreaking at the time, the film seems dated now, mired as it is in 1960s fashions, decor, cars, politics and social behaviors. Still, it’s an important movie, and I fear it will always be relevant, chronicling the interracial romance between Sidney Poitier and Katherine Houghton and cultural resistance to it.  The film is given substantial weight by the actors portraying Houghton’s parents, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn; both were nominated for Oscars, with Hepburn winning her second for the role. Houghton, by the way, is Hepburn’s niece; this was her first feature film role.

The film is given substantial weight by the actors portraying Houghton’s parents, Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn; both were nominated for Oscars, with Hepburn winning her second for the role. Houghton, by the way, is Hepburn’s niece; this was her first feature film role.

It is Tracy, however, who steals the show. Frail yet feisty as Matt Drayton, his lined, curmudgeonly face scowling with thought, it is he who eventually must bless the union of his daughter, or not. In a marvelously written, brilliantly performed eight-minute monologue Drayton holds court on the union — and makes all the sense in the world. It is impossible to tell how influential this monologue was in terms of the real world, but I think it certainly helped people feel increasingly comfortable with the idea, and it might just have changed a few minds. I’m sure that was the idea, and obtaining a powerful presence such as Tracy to moralize and embody the spirit of righteousness was a typically brilliant Stanley Kramer idea. Regardless, Tracy is at his level-headed best in that scene, which was the last he lensed for the film. He died just two-and-a-half weeks after finishing principal photography.

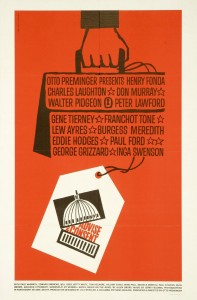

British by birth and an American citizen since 1950, Charles Laughton made his final film appearance brilliantly portraying a Southern senator in the all-star political melodrama Advise and Consent (1962). Director Otto Preminger had wanted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for that role, but after careful consideration King withdrew, opening the door for Laughton’s entry. A chameleon of an actor, Laughton based his speech patterns on a real-life Mississippi senator, coaxing him to read parts of the script into a tape recorder so Laughton could learn to nail the accent with authority. Laughton was often termed “hammy” by critics, so casting him as a Southern senator might easily have backfired.

British by birth and an American citizen since 1950, Charles Laughton made his final film appearance brilliantly portraying a Southern senator in the all-star political melodrama Advise and Consent (1962). Director Otto Preminger had wanted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for that role, but after careful consideration King withdrew, opening the door for Laughton’s entry. A chameleon of an actor, Laughton based his speech patterns on a real-life Mississippi senator, coaxing him to read parts of the script into a tape recorder so Laughton could learn to nail the accent with authority. Laughton was often termed “hammy” by critics, so casting him as a Southern senator might easily have backfired.

Instead, Laughton gives a penultimate performance — one that should have been an Oscar nominee — as a conniving political manipulator, a man with clout whose strongest desire is to control everything and everyone surrounding him. Sweltering in his white suit, Laughton waddles around Washington coaxing, cajoling and pressuring other people into following his wishes. Shortly after filming Laughton fell in his tub, was given a thorough examination and was discovered to have cancer. Even knowing he was ill, he agreed to play a key role in Billy Wilder’s comedy Irma La Douce, but his health deteriorated to the point that he could not undertake the project. He died before the end of 1962.

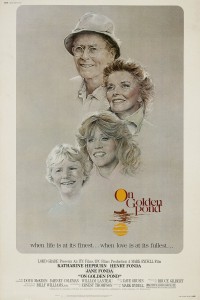

One actor who did win an Oscar in his final film is Henry Fonda, who plays old angler Norman Thayer, Jr., in On Golden Pond. Taking the role allowed Fonda to play opposite Katharine Hepburn for the first time, and with his daughter Jane Fonda, also for the first time. Hepburn also won an Oscar, her fourth, for the film, and Jane was nominated. Henry Fonda was known to be ill at the time of filming with heart trouble and he died about six months after winning the Oscar, which Jane accepted on his behalf.

Fonda’s persona is that of the American Everyman, but in On Golden Pond he’s merely a cantankerous, irascible old man. The film is sentimental but Fonda avoids sentiment as much as possible. He grunts dialogue, squints for effect and generally makes his character as irritable as can be. But underneath the grumpy exterior is a very vulnerable old guy who knows his days are numbered, and Fonda calls on this knowledge in his scenes with Jane; scenes which reflect all too accurately the rocky relationship they had in real life. Henry Fonda’s performance is the most memorable aspect of On Golden Pond and it is an apt, touching finale to a career which spanned half a century and quite a number of great performances and movies.

Some performers sign off in projects that are, in terms of quality, decent or better. Their goodbye performances may not evoke the same pangs of nostalgia and emotion that those listed earlier do, yet they are certainly worthy of respect and admiration. They include:

Jean Arthur in Shane (1953)

Ingrid Bergman in Autumn Sonata (1978)

Fredric March in The Iceman Cometh (1973)

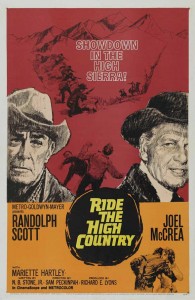

Randolph Scott in Ride the High Country (1962)

Myrna Loy in Just Tell Me What You Want (1980)

Judy Holliday in Bells Are Ringing (1960)

Tyrone Power in Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

Alan Ladd in The Carpetbaggers (1964)

Grace Kelly in High Society (1956)

Natalie Wood in Brainstorm (1983)

William Powell in Mister Roberts (1955)

Edward G. Robinson in Soylent Green (1973)

Audrey Hepburn in Always (1989)

Greta Garbo in Two-Faced Woman (1941)

James Dean in Giant (1956)

Ronald Reagan in The Killers (1964)

Vivien Leigh in Ship of Fools (1965)

Carole Lombard in To Be or Not to Be (1942)

John Garfield in He Ran All the Way (1951)

Gary Cooper in The Naked Edge (1961)

Betty Grable in How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955)

Judy Garland in I Could Go On Singing (1963)

Richard Burton in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984)

William Holden in S.O.B. (1981)

Lillian Gish in The Whales of August (1987)

Ann Sothern in The Whales of August (1987)

Pat O’Brien in Ragtime (1981)

James Cagney in Ragtime (1981)

Jessica Tandy in Nobody’s Fool (1994)

Maureen O’Hara in Only the Lonely (1991)

Robert Preston in The Last Starfighter (1984)

James Coburn in American Gun (2002)

Claire Trevor in Kiss Me Goodbye (1982)

Alexis Smith in The Age of Innocence (1993)

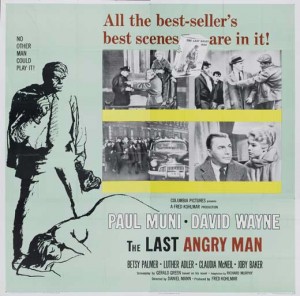

Paul Muni in The Last Angry Man (1959)

Lloyd Nolan in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

Loretta Young in It Happens Every Thursday (1953)

Claudette Colbert in Parrish (1961)

Marlon Brando in The Score (2001)

Karl Malden in Nuts (1987)

Unfortunately, some performers make foolish decisions that spoil, to some degree, their cinematic legacies. Whether it is bad luck, bad judgment or just plain bad, these performers did themselves no favors before checking out permanently or retiring before their time, or simply going out with a thud instead of a bang.

Errol Flynn in Cuban Rebel Girls (1959)

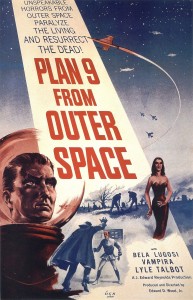

Bela Lugosi in Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959)

Mae West in Sextette (1978)

Gloria Grahame in The Nesting (1981)

Peter Sellers in The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980)

Boris Karloff in Sinister Invasion (1968)

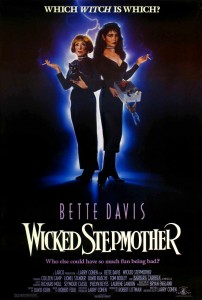

Evelyn Keyes in Wicked Stepmother (1989)

Bette Davis in Wicked Stepmother (1989)

Basil Rathbone in Hillbillys in a Haunted House (1967)

Lou Costello in The 30-Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959)

Susan Hayward in The Revengers (1972)

Pier Angeli in Octaman (1971)

Ronald Colman in The Story of Mankind (1957)

Fred MacMurray in The Swarm (1978)

Shirley Temple in A Kiss for Corliss (1949)

Veronica Lake in Flesh Feast (1970)

Laurence Harvey in Welcome to Arrow Beach (1974)

David Niven in Curse of the Pink Panther (1983)

Janet Leigh in Bad Girls From Valley High (2005)

Ida Lupino in My Boys are Good Boys (1978)

Cameron Mitchell in Jack-O (1995)

Gene Kelly in Xanadu (1980)

Eve Arden in Grease 2 (1982)

Joan Crawford in Trog (1970)

So not everyone can exit with elegance. Most performers fall in the middle like Lee Marvin in The Delta Force (1986); it’s serviceable but not memorable. Only a select few get the right project at the right time — the opportunity to say adieu and make a lasting impression at the same time. Hopefully some of today’s stars will join them with that success. (10:4).