Our first classic of 2014 is a police procedural shot on location in New York City back in the days when that fact was actually a big deal. The Naked City is truly a cinematic love letter to New York despite the fact that it involves some very seamy behavior by a few of its residents.

Our first classic of 2014 is a police procedural shot on location in New York City back in the days when that fact was actually a big deal. The Naked City is truly a cinematic love letter to New York despite the fact that it involves some very seamy behavior by a few of its residents.

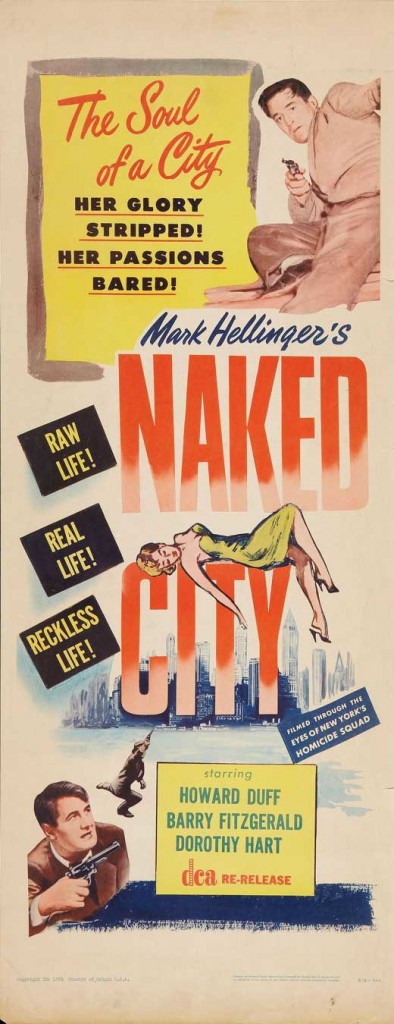

Produced — and narrated — by independent producer and former journalist Mark Hellinger, The Naked City is an unusual concoction of standard cop drama and documentary technique. Only the cop drama isn’t so standard; movie cops of that era rarely solved any cases because there were usually hard-boiled private eyes around to pick up the slack. But The Naked City uses deep research and an honest approach to create an authentic situation populated by believable characters, all shot on the very locations where the story occurs.

Those facts may not seem particularly impressive now, yet The Naked City was one of the earliest examples of an urban film shot entirely on location rather than shot on studio sound-stages in Hollywood. This required some trickery involving cameras hidden in vehicles, dark alleys and secretive city places, since there was little official aid in filming on New York City streets at that time. The script by Albert Maltz and Malvin Wald called for lensing in 107 specific locations from apartments to precinct houses to the Williamsburg Bridge. Even if the resulting movie were not particularly good, it would still be noteworthy for its rule-breaking style. Thankfully, the movie has many other rewards.

The story is deceptively simple. A young woman is found dead, presumed drowned, until facts prove otherwise. An investigation begins, blossoms as persons of interest are interrogated, then falters as leads wither on the vine. The smallest of clues provides a lucky break, followed by a quick progression of action as the case opens wide and races to its climax. That basic formula has been utilized in dozens, if not hundreds, of police procedurals and especially cop shows on television — and yet it is a formula that seems fresh as long as it is done with originality and intelligence.

Jules Dassin’s film is certainly fresh, original and intelligent. Rather than casting tough, handsome movie stars as the diligent detectives, the script follows reality by making the lead detective an elderly Irishman (portrayed by Barry Fitzgerald). None of the other homicide detectives are matinee idols, nor do they solve crimes in any sort of superhuman manner. The crime is solved by old-fashioned hard work, by checking every single fact and fitting it in with the thousands of other facts collected by the indefatigable police force. The key is how Lieutenant Dan Muldoon (Fitzgerald) follows practiced procedure as long as it works, then plays a hunch by his colleague Detective Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor) when it seems practical, and decisively puts together the final pieces of the evolving puzzle. Dassin’s film is resolutely logical as it follows suspects and detectives all around town, capturing moments and details of city life and, in the case of Jean Dexter, lonely city death.

The cops and detectives are largely unemotional about their work, it having become routine and mostly dull long ago. But they are professional, all working toward the shared goal of finding and capturing the wicked. Muldoon is an impish man who relishes small moments of humor which relieve the relentless itch of crimes unsolved, always knowing that there are more to come. He’s happy to mentor young detectives like Halloran, although he refuses to mollycoddle them.

The case progresses gradually from point to point, just like in real life, and just as deliberately. Screenwriter Malvin Wald spent a month with NYC detectives learning the ropes, absorbing the atmosphere and detailing the techniques that would lend his tale its authenticity. When producer Hellinger pressed Wald for a specific plot Wald recounted several unsolved cases that could serve as the main story; to his shock, Hellinger discovered that he was not only familiar with one of Wald’s case histories, but he had actually known the victim. That familiarity decided the issue and set the movie in motion.

Hellinger later had cold feet about the project because he was nervous about the experimental technique and unsure of its commercial appeal. Eventually he changed his mind, took the gamble and willingly placed his name and reputation behind it. It is Hellinger who provides the narration throughout the film, gently coaxing the detectives toward clues, chiding characters for their choices and rather obviously indicating things to the audience. Hellinger was pleased with the finished product when he viewed a final cut on December 20, 1947. He reportedly told his publicist “That’s my celluloid monument to New York. I loved it!” Hellinger never witnessed the public’s reaction, however; he collapsed of a heart attack the following day and died at the age of just forty-four.

Hellinger’s legacy as a producer includes some terrific titles, such as the Humphrey Bogart films It All Came True, Brother Orchid, They Drive by Night (all 1940), High Sierra (1941), Thank Your Lucky Stars (1943) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). He was just hitting his stride in the late forties, having recently made The Horn Blows at Midnight (1945), The Killers (1946) and, with director Jules Dassin at the helm, the great prison drama Brute Force (1947). Despite his initial misgivings about the format the independent producer recognized the value of the ultra-realistic, semi-documentary approach utilizing on-location lensing and became convinced that, even while sometimes problematic, the results were worth the headaches.

After angering Hellinger by making his chief detective 65 and Irish (because so many NYC detectives were older and of Irish descent), it was screenwriter Malvin Wald who suggested Barry Fitzgerald for the lead. The producer was sure that Fitzgerald, who had recently won an Oscar for Going My Way (1944) would not be interested, but Wald persisted and the two of them persuaded Fitzgerald to accept the role. That casting choice is a pivotal reason why the film works as well as it does; a younger, perhaps more strident actor — such as James Stewart, who Hellinger originally wanted — might have made the drama more of a crusade.

Fitzgerald’s Muldoon is wise, wry and patient. For younger viewers, let me put it this way: he’s like the Gandalf of the police force, without the hair. When clues dry up and the case bogs down, Muldoon pulls out his pipe, lights it and uses his intuition and imagination to illuminate new avenues to explore. Barry Fitzgerald was a fine actor who could, in certain roles, really push the sentimentality. He tones down that tendency here, delivering a very serious performance that is all the more delightful because of the occasional quips he delivers. He’s even the butt of the joke on more than one occasion. His boss, Captain Donohue (Frank Conroy) suggests he again use Halloran as a partner and asks how the young detective is doing. “He’s makin’ the same mistakes I made at his age,” replies Muldoon. Without missing a beat Donohue says, “Too bad. I thought he showed promise,” and then smiles at his old friend.

The specific case that unspools within The Naked City is intriguingly complex, first leaning one way, then another, until the truth is revealed. I won’t delve into its details except to say that people are not always who they say they are in the naked city. The case is actually, loosely, based on that of the so-called “Broadway Butterfly,” Dorothy “Dot” King, who was murdered in 1923. Her killing was a rather sensational news story of its time, covered in the press by none other than Mark Hellinger and Walter Winchell, who actually visited the crime scene and saw the body, but the case was never truly solved. Three separate movies have used the Dot King murder as close inspiration: the Philo Vance murder mystery The Canary Murder Case (1929), the melodrama The King Murder (1932) and The Naked City.

Wald and screenwriter Albert Maltz, who gave the story its final polish, did not adhere closely to the real case’s facts. Wald had studied hundreds of cases in his research and cobbled together a story with elements from several of them. Since the King murder had been committed so many years earlier Wald concentrated on updating the police methods used to gather and analyze so much data, and detailing how such a confusing crime could be solved using standard methodology aided by the most modern technological advances. That technology looks incredibly dated today, whether it be the plug-in telephone switchboard or a card file of robbery suspects or a simple blackboard with names written in chalk without any other elaboration, yet those tools served their purposes then. In the end, it is the man on the street — the beat cop or the detective following up a lead — which brings the case to its climax, and that is just as it should be.

In addition to Fitzgerald and Don Taylor there are several other familiar faces in the cast. Howard Duff, Ted de Corsia, Tom Pedi, Dorothy Hart, Anne Sargent, Frank Conroy and House Jameson boast substantial roles, but sharp eyes can also spot Paul Ford, Kathleen Freeman, James Gregory, John Marley, Arthur O’Connell, Nehemiah Persoff, Molly Picon and John Randolph, among others. Gregory, Persoff and Randolph all made their film debuts in The Naked City.

The film was very well received upon its release on March 4, 1948, especially on its home turf. Hellinger’s friend Walter Winchell called it “one of the most thrilling motion pictures ever made.” Critics praised it and crowds made it a popular hit, grossing more than $1.6 million in its first month of release. It was later nominated for three Academy Awards, winning two: Original Story (Malvin Wald) and Film Editing (Paul Weatherwax). Such accolades, however, would not mark the end of The Naked City‘s “eight million stories.”

Television brought new life to the premise when, in 1958, “The Naked City” began a four-season run on ABC with John McIntire as Muldoon and James Franciscus as Halloran. Oddly, those two characters and its half-hour format only lasted through the first season; when the second season began it featured hour-long episodes with Harry Bellaver, Horace McMahon and Paul Burke in the major detective roles. Like its predecessor it was filmed entirely on location in New York, becoming the first network series to be produced in such a manner.

Is The Naked City a classic? Yes. A minor classic perhaps, one whose influence was heavily felt during the neo-realism movement of the late forties and early fifties, leading to fact-based procedurals such as “Dragnet” as filmmakers took notice of its gritty style and rejection of sensationalism. Its influence has faded over the years as so many other movies and television series have followed its lead, yet its innovations are still thoughtful today — whether it be Mark Hellinger speaking the opening credits or hiding cameras in vans and news stands to capture passersby in unsuspecting moments as the main actors move among them. It is a very good film with a few dated aspects that holds up very well. My rating: ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 5 January 2014.