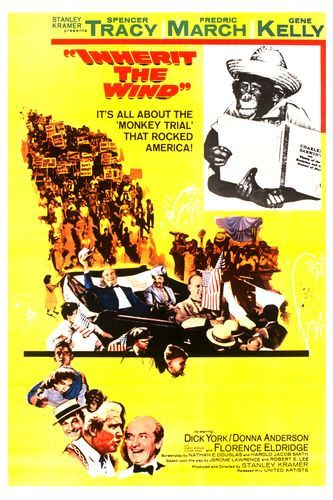

Our eighth classic of 2014 is the first film adaptation of a famous play which dramatizes one of America’s most infamous court cases. That film (and play) is Inherit the Wind (1960). The distinction I am noting that the film dramatizes the play is important — while the actual court case (the so-called “Scopes monkey trial”) is an historic event, the play that followed is even more famous, and has been accepted by many as history in the place of real history. The 1955 play, written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, has been performed thousands of times since its publication, from high schools and regional stages to the bright lights of Broadway. The play condenses and dramatizes many of the elements, themes and personalities of the trial, but does so for dramatic effect. By creating new persona for the major players (Clarence Darrow becomes Henry Drummond, William Jennings Bryan becomes Matthew Harrison Brady, John T. Scopes becomes Bertram Cates and H. L. Mencken becomes E. K. Hornbeck) the play — and resulting film, and, later, telefilms — intend to explore the milieu of the trial while freeing themselves from the burden of sticking like glue to historical fact.

Our eighth classic of 2014 is the first film adaptation of a famous play which dramatizes one of America’s most infamous court cases. That film (and play) is Inherit the Wind (1960). The distinction I am noting that the film dramatizes the play is important — while the actual court case (the so-called “Scopes monkey trial”) is an historic event, the play that followed is even more famous, and has been accepted by many as history in the place of real history. The 1955 play, written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, has been performed thousands of times since its publication, from high schools and regional stages to the bright lights of Broadway. The play condenses and dramatizes many of the elements, themes and personalities of the trial, but does so for dramatic effect. By creating new persona for the major players (Clarence Darrow becomes Henry Drummond, William Jennings Bryan becomes Matthew Harrison Brady, John T. Scopes becomes Bertram Cates and H. L. Mencken becomes E. K. Hornbeck) the play — and resulting film, and, later, telefilms — intend to explore the milieu of the trial while freeing themselves from the burden of sticking like glue to historical fact.

The play was written thirty years after the famous trial, and written in response to the growing menace of McCarthyism in America (that’s according to the authors). It’s all about freedom of speech and freedom of thought, not to mention founding efforts in education upon science. The trial centered on the right of a teacher (John Scopes; Cates in the play and film) to teach evolution as well as creationism. Not instead of, but in addition to. Scopes was charged with violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which made it illegal to teach evolution in any state-funded school. Scopes volunteered to act as the defendant and a trial was held to deliberate bring attention to the issue. Three-time presidential hopeful William Jennings Bryan was brought in to prosecute the case and Clarence Darrow was hired by the Baltimore Sun to elucidate Scopes’ defense. Sun columnist H. L. Mencken covered the trial for the paper, which made national news as it culminated. Scopes was found guilty and fined $100 (which Bryan offered to pay), and the case was quickly concluded (the guilty verdict, which Darrow had asked for in order to appeal to the state Supreme Court, was later overturned on a technicality). Five days after the trial, William Jennings Bryan died in his sleep.

The play and films portray the trial in direct, simple terms — practical common sense and scientific progress embodied by defendant Bert Cates (Dick York), attorney Henry Drummond (Spencer Tracy) and writer E. K. Hornbeck (Gene Kelly) versus narrow-minded, hate-filled fundamentalist Bible-thumping conservatism embodied by attorney Matthew Harrison Brady (Fredric March), preacher Jeremiah Brown (Claude Akins) and a town full of righteous bigots who threaten to hang the teacher who dares teach their kids Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. That’s just how the film paints the picture, folks, setting up the sentiment squarely in the corner of progress and freedom. It actually works better on stage as an intellectual exercise, where the trial can serve as a metaphor for the dangers of a mob mentality, a demand for calm rational thought and a clarion call for the rights of an individual to be recognized. As effective as the film is, it actually inflames emotions to the point that its message can be rather easily missed or misconstrued. It isn’t really a battle between science and Biblical teaching at all; it’s about the absolute need to allow people to think for themselves without being prosecuted for their beliefs.

The play was a big hit and it was only a matter of time before a movie was made. Producer-director Stanley Kramer purchased the play’s rights and cast it with the two leads he first considered. In his book A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: A Life in Hollywood, Kramer explains his reasoning regarding the play’s impact: “To me at least, the whole story is about freedom of expression, its importance in our society and the challenges to it. The Scopes story is important because the pro-religion, anti-science side in this instance refused to examine the ideas of its opponents.”

Kramer actually visited Dayton, Tennessee, where the trial had taken place thirty years earlier, and took great pains to bring the town to life in his movie. Oppressive heat overhung the original trial; Kramer emphasizes discomfort and sweat in almost every shot. Note the fans that people constantly wave in the courtroom, emblazoned with the name of the local funeral home that supplied them. The film also opens up the play a bit, especially at the beginning as the protagonists arrive in town, and in the evenings. One particular evening scene presents Brady and Drummond sitting on a porch in rocking chairs, rocking at different speeds to simulate their differences of opinion, as Drummond relates the story of how he desired a rocking horse named Golden Dancer when he was a child. Another outdoor sequence is a sermon led by Reverend Brown, which quickly escalates to a call for blood, only defused by Brady and his wife Sarah (Florence Eldridge, who was Fredric March’s real-life wife). The film also expands the characters of Reverend Brown and his daughter Rachel (Donna Anderson), Bert Cates’ colleague and fiancé.

Given the passions that run wild around the subjects of its drama, it is not surprising that the film was picketed in some areas upon its release in 1960. There had been calls for United Artists to abort the project while in development, and, according to Kramer, the studio would have been quite willing to do so, but he was adamant that a good movie could be made of the material, so he was allowed to continue. Despite positive reviews and some award recognition (four Oscar nominations, no wins), the film was not a hit. Kramer claims it lost money, one of his few productions to do so.

Whatever one’s feelings about the debate between science and religion there is no debate that Inherit the Wind is a film with wonderful acting. It is an actor’s showcase for both Spencer Tracy (who was nominated for his seventh Oscar, losing to Burt Lancaster in Elmer Gantry, another film with an anti-religious slant) and Fredric March, who was inexplicably not nominated. March dominates the screen with both pomposity and wit, with a ready answer for almost any question. It’s a great portrayal, and a perfect foil for Tracy’s gruff rustic charm. More controversial was Kramer’s first choice for the writer, Hornbeck. Gene Kelly essays a rare dramatic role oozing cynicism and acidic commentary about the local yokels. It’s such a change of pace for him that some, perhaps many, viewers have difficulty accepting him. I think he’s terrific, especially at the very end when Drummond has had enough of his posturing and tells him off, telling the writer that he will die alone and without any mourners. Hornbeck gently replies that no, he won’t be alone. Drummond will be there. It’s a great moment.

Inherit the Wind is an unusual courtroom drama. In a hostile environment the defense has obstacles galore, beginning with jury members who feel their way of life is being attacked, and a judge (Harry Morgan) who refuses to allow the defense to call any scientific witnesses because that would being evolutionary science into the case. So Drummond does the only thing he can, which is to focus on the Bible, and calls upon Matthew Harrison Brady to take the stand. It’s an unusual move that follows history, as Clarence Darrow used the tactic against William Jennings Bryan in the original trial. What viewers remember most about this movie is the often tense, sometimes jovial back-and-forth banter between Drummond and Brady about Jonah and the whale, the length of a day and whether people still “begat” in the same way as they once did. “I don’t think science has improved that any,” replies Brady. Ultimately, Drummond shifts the focus from the Bible to Brady’s interpretation of it, and Brady’s ego in presenting those conclusions to the public.

This is certainly entertaining stuff, and it is acted to the hilt by two magnificent actors. It follows the path of the original trial, and yet I cannot help but feel that it does an injustice to the debate. It is legal trickery, tomfoolery, to bait the opposition into humiliation on the stand involving personal belief, and does little to expand discussion. Darrow (and by extension, Henry Drummond) felt he had no choice, given the court’s restrictions, and it was certainly newsworthy, but it comes across as a stunt rather than a solid legal tactic. The judge of the case felt so, as well, because the next day he expunged Bryan’s testimony from the record, calling it irrelevant, and thereby preventing Bryan from calling Darrow to the stand in response. It is memorable, but I cannot help but feel that this is a case where real life failed to be as effective as fiction. Stranger, certainly, but not as dramatically satisfying.

Nevertheless, Inherit the Wind is a top-flight film. For the most part Stanley Kramer looked for social causes to explore in his movies, and this certainly qualifies. Critics often found his approach rather obvious and heavy-handed, which I cannot deny or defend, and yet I really like and respect most of his films that I’ve seen. Kramer was great with actors, knew how to put stories together and how to bring elements in place to create authentic, realistic drama. He was pretty good with comedy, too, for that matter.

Is Inherit the Wind a classic? You betcha. It has been remade three times since this iteration — a 1965 telefilm with Melvyn Douglas, Ed Begley and Murray Hamilton; a 1988 telefilm with Jason Robards, Kirk Douglas and Darren McGavin; a 1999 telefilm with Jack Lemmon, George C. Scott and Beau Bridges — yet this version remains the gold standard by which the others are measured. It is the last feature film of Dick York, who moved into television and became famous as the first Darren Stevens on “Bewitched.” It was the first film to be shown as an in-flight movie when TWA debuted that service in 1960. It has, for better or worse, entered into the public consciousness as the most recognized representative of the Scopes monkey trial, and it is a damned entertaining movie. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 26 March 2014.