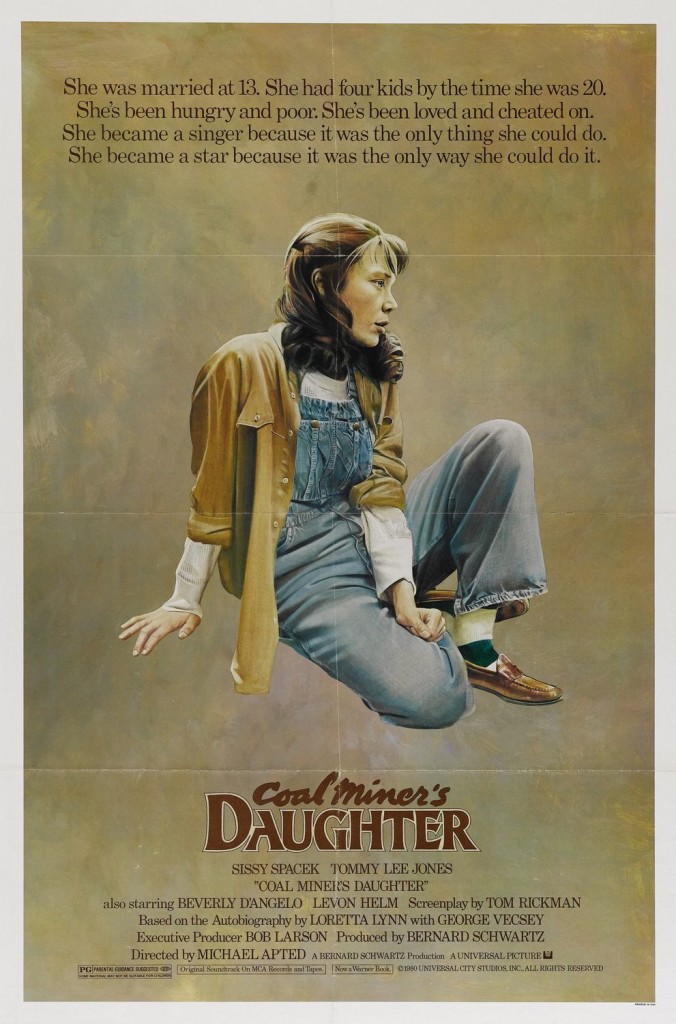

Our tenth classic of 2014 is the dramatic musical biography of country and western singer Loretta Lynn, which shares the same title as her famous autobiographical song, Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980). The film stars Sissy Spacek as the singer, and her performance was so perfect that she won the Best Actress Oscar for it. Spacek had been personally chosen by Lynn because of her freckled features, and she accompanied Lynn on tour and visited her many times before the movie went into production so that she could portray the singer as convincingly as possible. Obviously she did her job splendidly –as did director Michael Apted — in recreating Loretta Lynn’s (nee Webb) rural Kentucky roots, her romance with rough-edged World War II veteran Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn (Tommy Lee Jones) while still a young teenager, her maturation into a capable woman, and her unexpected detour into singing. Life is a winding, crazy journey for many people, an odyssey, and Loretta Lynn’s biography proves once again that life is often, and perhaps usually, stranger than fiction.

Our tenth classic of 2014 is the dramatic musical biography of country and western singer Loretta Lynn, which shares the same title as her famous autobiographical song, Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980). The film stars Sissy Spacek as the singer, and her performance was so perfect that she won the Best Actress Oscar for it. Spacek had been personally chosen by Lynn because of her freckled features, and she accompanied Lynn on tour and visited her many times before the movie went into production so that she could portray the singer as convincingly as possible. Obviously she did her job splendidly –as did director Michael Apted — in recreating Loretta Lynn’s (nee Webb) rural Kentucky roots, her romance with rough-edged World War II veteran Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn (Tommy Lee Jones) while still a young teenager, her maturation into a capable woman, and her unexpected detour into singing. Life is a winding, crazy journey for many people, an odyssey, and Loretta Lynn’s biography proves once again that life is often, and perhaps usually, stranger than fiction.

A great many Hollywood biographies either fudge the facts of their subjects’ lives in favor of sensationalism and sentiment. Still others simply make stuff up without ever checking the facts at all, or focus on a very specific, limited area of their subjects’ careers in order to address certain themes, political points or specific historical contexts. Coal Miner’s Daughter does none of this; its approach is to represent Loretta Lynn’s life as closely as it was described in her best-selling autobiography without ebullient fanfare, squishy sentiment or programmed pathos. Naturalism is the key word here, and the movie is a great one because it is so authentically, convincingly, refreshingly naturalistic.

To helm the project, Universal found exactly the right person, Michael Apted, a Britisher with a fondness for very personal stories and a flair for developing his subjects’ natural appeal on film. Coal Miner’s Daughter was his fifth feature film, but Apted had already begun what would become a lifelong task, a documentary series that began in 1964 with Seven Up! and would revisit the same real people every seven years to chronicle the paths their lives had taken. The most recent installment was 56 Up in 2012, the eighth time the same group of people were interviewed about their lives. Apted was a researcher for Granada TV and chose the children for the project in 1963; he has since directed every seventh-year segment beginning in 1970. And while Apted has helmed some marvelous big-budget blockbusters in his day (Gorky Park, The World is Not Enough), he specializes in more personal stories, often rural in locale and focusing on female characters (Gorillas in the Mist, Nell, Enough, Blink). He was a great choice for this biography, and it may be the best of his feature film career.

Consider this fact: although the protagonist is singer Loretta Lynn, she barely sings at all until the second hour of this 125-minute movie. Loretta’s raw talent is established as she sings lullabies to her siblings, and later her own children, but she doesn’t sing professionally until Doolittle essentially forces her to in Washington after she’s had four kids. Because Lynn’s story was so well known, her singing success was to be expected — at some point — so Apted could focus his energies on establishing her character and unusual circumstances in order to frame just how much fame surprised her and changed her, as well as her relationship with her husband.

The surprise of the movie to me is just how much of it is really about Doolittle Lynn (also known as Mooney, from an short-lived attempt at moonshining). Doolittle is charismatic and cocksure, setting his sights on pretty young Loretta (who was just 15 when they married) and prevailing upon her parents that the feelings he has for her are genuine. More importantly, she shares the same love for him, and doesn’t care about the difference in age or maturity. Doolittle struggles to adapt to Loretta’s naiveté and innocence, yet his true nature almost always works in their favor. He makes mistakes, specifically when he slaps her a couple of times, and the film doesn’t shy away from those moments, which are ugly. But it also shows tender times and great kindness on Doolittle’s part. It presents a fully-fleshed portrayal of a real human being. Tommy Lee Jones is terrific in the part that might have been Joe Don Baker’s. Jones was beginning to get bigger roles in lesser movies, but this was really his big break, and he is just as impressive as Sissy Spacek in terms of presence and performance. In fact, Jones appears very early and dominates the first half as the wild rover hellbent on staying out of the coal mines that are slowly killing Loretta’s hardworking father (Levon Helm). This larger-than-life persona gives the first half a shot of energy, and then provides an intriguing dramatic contrast as Loretta discovers that people like to hear her sing and her fame supersedes Doolittle’s ability to rule the family.

It is, in fact, Doolittle who buys her a guitar as an anniversary present and then encourages Loretta to sing publicly in the first place. His efforts to get her up on stage, and then to record and promote her first songs, are the comic bridge between the poverty of the story’s first half and the Nashville glitz of the second half. That section, as the couple crisscrosses the country in their car, taking their single to various radio stations before finding their way to the Grand Ole Opry, is hugely endearing and entertaining. The tone is light and lively, the triumph is heartfelt when they discover that Loretta’s first single is number 14 on the Billboard chart (although it isn’t quite as transcendent as the similarly-themed scene in That Thing You Do!). That bridge is exactly how most movie producers would envision it in just about any movie about making it in the music business, and it is put across spectacularly well. But the rest of the movie isn’t as jovial and lighthearted.

Apted keeps the emphasis on the characters. Before the bridge, it’s the development of the love story and Loretta’s maturation into a woman who can handle a husband and family, and more. After the bridge, it demonstrates how fame ruptures the relationship, driving Doolittle away from Loretta because he no longer has much to do. She befriends singer Patsy Cline (the great Beverly D’Angelo) and begins to alter her personality to her new surroundings and circumstances. She quickly learns to spend money and begins to take other people’s advice as much as Doolittle’s. Their relationship erodes to the point where it should end, and yet once again Doolittle’s authentic love for Loretta prevents him from being a total jackass. He adapts, she adapts and the marriage is saved. He accepts his role as her caretaker although he would much rather be outside driving a bulldozer, doing things with his strong hands. Time and time again, he is there for her, even when she finally succumbs to the pressure of too many shows and too many pills to keep herself going.

The movie does gloss over Loretta’s mental breakdown once it has occurred, omitting the usual scenes of struggle and recovery. In its place are three fairly long takes of the quiet Lynn homestead in Tennessee, which, I think, symbolize Loretta’s need for peace and tranquility. Without much further ado Loretta returns to the stage for the big finale, her rendition of the title song while the end credits role. The rather abrupt ending is probably the movie’s biggest fault, undoubtedly due to the fact that the two-hour mark has just been passed. Unlike other show-biz biographies, this one doesn’t linger on concert scenes. Some of Loretta’s songs are recreated — and they are recorded live, without lip-synching — but none are shown or heard full-length until the end, which is essentially a montage. And then behind the end credits many of them are heard again, in shortened versions. The filmmakers are fairly certain that her songs are familiar; they have spent their time working to impart the humanity behind the music rather than the music itself.

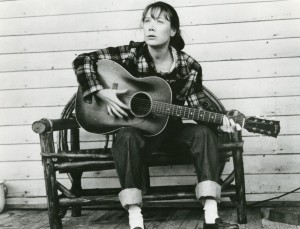

One of the most appealing aspects of the picture is that everything is so homespun. Whether it’s Loretta’s parents’ home in Butcher Hollow, Kentucky or her first married home in the state of Washington, or her big estate in Hurricane Mills, Tennessee, much of the personal action takes place at these locales, or near them. Loretta learns to play the guitar and write songs while doing the laundry and taking care of the children in Washington, while Doolittle stays up at night typing letters to accompany record demos to radio stations. There’s always cooking, or housework, or kids scrambling around because that was the reality. The career which eventually dominated Loretta’s life at first had to fit between loads of laundry and after the kids were put to bed. Keeping the emphasis on the everyday reality and in these real locations is paramount to the film’s verisimilitude. And it works.

Two aspects of Loretta’s life are omitted by choice. It is hinted that Doolittle was not exactly faithful to Loretta, but his infidelities are not exposed and examined in the way that they undoubtedly would be today. For those who need to know, read the three autobiographical works penned by Loretta. The second aspect is her famous duet partnership with Conway Twitty that proved to be exceptionally popular during the 1970s. Twitty is not even mentioned, I believe, because the film wants to tell her story exclusively, balancing her role with that of Doolittle. Universal probably felt that covering the duet partnership, as successful as it was, would have diluted the focus and not provided much dramatically.

The music which is so important to the life and legend of Loretta Lynn is delivered in the second half, when Sissy Spacek belts out several of Loretta’s biggest hits and ends the film with the wonderful title tune. Spacek did indeed sing the music live on camera, having studied Loretta in person to note how they were sung. In fact, Spacek had begun her show business career in New York as a singer, only turning to acting because she could never quite get the “big break” that so many singers need to reach commercial success. Spacek’s performances are no less than great, not just mimicking Loretta’s style but locating each lyric’s significance and relating it directly to the audience. Her singing is as good or better than her acting, and it is no wonder she won the 1980 Best Actress Academy Award — as well as the parallel Golden Globe award and accolades from around the world. Beverly D’Angelo also sings her Patsy Cline songs in the same manner, and she should have also been critically recognized with the same praise.

Coal Miner’s Daughter was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Actress, Adapted Screenplay, Editing, Cinematography, Sound and Art Direction-Set Decoration. It’s only win was for Sissy Spacek. However, Spacek helped create Oscar history that night. As she took the stage for her award, Loretta Lynn sat in the audience. Lynn had, for years, been promoting Sissy Spacek as the actress who was going to play her in a movie, and her enthusiasm for the movie had opened many doors in the country-western world for the filmmakers. Likewise, as Robert De Niro took the stage to accept his Best Actor award for Raging Bull, boxer Jake La Motta sat in the audience. It is the only time that the two major actor winners won for playing real people, and those real people were in attendance.

Is Coal Miner’s Daughter a classic? Yes! It’s one of the best films of 1980; it’s the best of the biographies of country-western singers that followed (Sweet Dreams, Walk the Line, Ray) as well as all the pseudo-biographical dramas in the country-western genre (Tender Mercies, Crazy Heart, Country Strong, Honkytonk Man, Pure Country, Falling from Grace, etc.). It’s a naturalistic marvel of a movie with great performances and terrific music. It’s an uplifting story that proves that anyone with talent and hard work can find success and, sometimes, happiness, doing the thing that he or she loves. It’s a celebration of music and romance and Americana, even though it was directed by a Britisher who didn’t particularly enjoy country music. It’s a wonderful movie. ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 7 June 2014.