The Ten: (arranged chronologically)

1955 Henry Fonda, Mister Roberts Actor

1956 Eddie Albert, Attack Supporting Actor

1956 Jack Palance, Attack Actor

1962 Robert Mitchum, The Longest Day Supporting Actor

1964 George C. Scott, Dr. Strangelove… Actor

1970 Karl Malden, Patton Supporting Actor

1980 Lee Marvin, The Big Red One Actor

1986 Clint Eastwood, Heartbreak Ridge Actor

1987 R. Lee Ermey, Full Metal Jacket Supporting Actor

1996 Denzel Washington, Courage Under Fire Actor

In 1999 (Volume 1, Issue 2) I wrote an article regarding ten horror performances which, in my opinion, were unjustly ignored by Academy Award voters. In 2008 (Volume 10, Issue 2) I reprised the idea with another ten performances, also overlooked by Oscar voters, this time in war films. This is an updated reprint of that 2008 article.

More than 1300 film performances have been nominated for Oscars over the years, but relatively few have been from war movies. Academy favorites have traditionally been epic historical pageants (which, indeed, may contain war scenes), semi-factual biographies, and important social dramas. And while a goodly number of war films have been Best Picture nominees and won in various technical categories, their performers — and virtually every major male Hollywood star has made war films — are usually overlooked. But not here.

By definition this will be a male-only list. Not that there aren’t worthy female roles in war films, but history has provided a minuscule number of them. War is by nature largely a male activity and certainly is so in cinema.

My main criteria for this list, other than the excellence of the performances, is that the roles must conform to the notion of men in uniform. To cast a wider net would unnecessarily dilute the focus of this article. I could have, for instance, chosen Richard Gere for his trainee role in An Officer and a Gentleman (1982), but I finally decided that his character was not on “active duty,” as these others are, and so could not be compared honestly with the others. That is a distinction I am making for this article.

Another decision I made is to restrict the choices to American roles. I seriously considered adding George Peppard for his role in The Blue Max (1966), and Jurgen Prochnow for his role in Das Boot (1982), but then felt that their inclusion would somehow diminish or soften the definition and boundaries of this group. Cases can certainly be made for these actors and others, but these are my parameters.

If Oscar history could be rewritten (and in many cases it should be!), I feel that these ten performances ought to take their rightful places in the Oscar pantheon.

Henry Fonda

as Lieutenant

Doug Roberts,

U.S. Navy

Henry Fonda had originated the title role in the play Mister Roberts by Joshua Logan and Thomas Heggen (based on the novel by Heggen) on Broadway, and had won a 1948 Tony award for his interpretation. Yet he was not the producers’ initial choice to play the part in Mister Roberts.

Fonda was almost fifty as production began, so the producers decided a younger man was needed. Marlon Brando was tied up, Tyrone Power and William Holden both chose not to participate and, with no star to be found, the producers gave Fonda the okay. Director John Ford was delighted; he had wanted Fonda from the first. Strangely, however, once production began they failed to agree on Fonda’s character interpretation and even came to blows in a production meeting. John Ford was replaced.

Mervyn LeRoy assumed directing chores, with Joshua Logan refilming certain scenes after LeRoy had finished his work. As should be evident, all was not smooth sailing for the ballyhooed production of Mister Roberts.

Yet despite all the turmoil and problems, the film itself is pretty good, if not great. Jack Lemmon steals the show as Ensign Pulver, and won an Academy Award for his effort; William Powell is terrific in his final film role as world-weary Doc and no captain has ever been as blustery as James Cagney. I almost picked Cagney as yet another snubbed Oscar recipient for this film, but there was just too much competition. And at the center of the storm is the unflappable, ever stalwart Henry Fonda, doing things his way. Having enacted the role for more than three years on Broadway, he felt he knew more about it than anyone, including John Ford. He was probably right; his presence, stability and patriotic yearning for action give the movie its foundation of power and clarity.

Fonda is perfect as Lt. Roberts, an officer on a third-rate cargo ship as far away from action in World War II as it is possible to get. Roberts wants his time in the Navy to mean something; he wants to contribute. He asks for transfers, which are always denied because he is the officer keeping the Reluctant running efficiently. Roberts tolerates all the nonsense aboard ship because he likes the men (they love him) and his optimism that someday, somehow, he will see action, will not permit him to take his responsibilities lightly. He is, like so many of Fonda’s signature roles, a man of patient honor and bellwether integrity.

But playing such a nice guy would be boring. Fonda transforms Doug Roberts into a real guy, with believable feelings, outbursts of emotion and a sly sense of humor. Roberts’ attitudes become the attitudes of the crew – if he is affable, they are okay. When he is perturbed, they are upset. And in the final scenes, after Mr. Roberts is finally cast off of the Reluctant, his fate affects every man on board as if he were their father. Fonda never sentimentalizes his performance; he just inhabits the character, which, after all, is the essence of great acting.

Eddie Albert

as Captain

Erskine Cooney,

U.S. Army

At the other end of the dramatic spectrum is Eddie Albert’s turn as cowardly Captain Cooney in Robert Aldrich’s anti-war diatribe Attack in 1956. As I wrote in my review of the film in Lee Marvin: His Films and Career, “Attack was Albert’s thirty-fifth film, and nothing he had done before had prepared audiences for the brittle, indecisive, spiteful character that Albert presented them.” Such startling career turns occasionally result in industry accolades, wider audience acceptance and greater recognition. This did occur with Albert, but a second Oscar nomination was not part of his career development at that time.

Captain Cooney is near the top of cinema’s most despicable cowards, barking bravely to cover deep-seated fear of inadequacy instilled by his domineering father. Unfortunately for the men under his command, Cooney is never seriously reprimanded for his cowardice nor replaced, all because his father is an important man and his superior officer (Lee Marvin) wants to curry his father’s favor after the war. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to collect favors from a guy who was sacked for gross incompetence.

Thus, Cooney is retained, though Marvin’s character warns him to get his act together and take care of his men. Cooney, however, does not. He again puts men at risk, refuses to attempt to rescue them and finally breaks down when Lt. Costa (Jack Palance) tells Cooney coldly that he will return just to kill him. Facing a certain death, Cooney finally finds foolhardy bravery and runs through the streets of an occupied town, screaming, shooting Germans as he rants and raves. He finds the remainder of his men and, amazed that he is still alive, suggests they surrender to the Germans. Then he insists on surrender, only to be interrupted by Costa, mortally wounded, back for his revenge. Cooney’s fate is such that the Department of Defense refused to cooperate in the making of this war film, the first time they had done so and held their ground. The DOD felt that Cooney’s character was blatantly detrimental to the armed services, so refused to lend Aldrich men, equipment or matériel.

Albert brings Cooney to vivid life, avoiding caricature in his portrayal of inexorable neurosis. Trapped in the Army that he dislikes and within a body he can barely control, Cooney is a breakdown waiting to occur. Albert builds Cooney’s nervous tics and bombastic style of leadership into a human time bomb. Many popular actors would avoid such a contemptible part, but Albert revels in its levels and challenges. He would play nuts again, most notably in Captain Newman, M.D. (1963), but never as floridly and brilliantly as he does in Attack. It was a complete role reversal for him, and he delivers a dazzling portrayal.

Jack Palance

as Lieutenant

as Lieutenant

Joe Costa,

U.S. Army

The main character in Attack, of course, is Lieutenant Joe Costa (Jack Palance), the intense, usually angry soldier who vows to take matters into his own hands if Captain Cooney continues to sacrifice American soldiers mishandling his command. Costa has sound reason for his anger; many of his men are no longer living due to the captain’s cowardice.

Costa is, admittedly, something of a two-dimensional character. He is either fuming at the injustice of the war or trying to handle his assignments as honestly and directly as he can. He’s a serious soldier and he’s lived long enough to know how to best survive and get his men through the worst of war. All he asks is sensible, defendable strategy and slow, steady progress. As such, he is the best of every soldier who has ever gone to war.

Where Palance excels in the role is the intensity factor and an absolute certainty that he means what he says. Palance has always been a passionate performer, but in Attack the man is a sheer force of nature. Costa is run over — by a tank — and yet he crawls onward and returns for revenge. It is also interesting that Palance, with his hard, angular face, anguished eyes and indestructible spirit is the symbol of choice for Aldrich.

In his later career, Palance tended to augment his performances with extraneous and even hammy dialogue delivery and mannerism; there is little of that here. Aldrich knew how to control his volatile star and coax the best possible, most controlled performance from him. Palance is at his best in Attack, just three years removed from his sinister, Oscar-nominated turn in Shane. Aldrich did his best to make Jack Palance a mainstream star, hiring him for three films, and almost succeeded. It’s our loss that Palance was not better utilized during his career, as he is here.

Robert Mitchum

as Brigadier General

Norman Cota,

U.S. Army

From a cast of 48 international stars (and others who had yet to become stars) it might seem difficult to locate one who stands above and apart. But that is not the case with The Longest Day, the epic 1962 chronicle of the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Virtually all of the performers are solid or better, but Robert Mitchum steals the show as Brigadier General Norman Cota, the man in charge of getting his men off of Omaha Beach.

Cota landed on the beach in the second wave of soldiers and was one of, if not the, highest ranking officers in the line of fire. As progress is being made elsewhere, his men are pinned down on Omaha until Cota takes charge, gathering engineers and steering them toward a gigantic concrete wall/bunker that blocks the way. Cota instructs his engineers to use a Bangalore torpedo to clear a path to the wall, which they do. The men then demolish much of the wall with high explosives. Once the men push through, Cota patrols the beach, ensuring that things are running smoothly heading inland, and it is his words which finish the film: “Run me up that hill, son.”

The filmmakers used General Cota as a figurehead of calm, clear-headed leadership on the chaotic beach, and gave Cota dialogue which may or may not have actually been spoken by the general. To a soldier who has dropped his rifle he says, “Well don’t you think you better go back and get your rifle? You’re gonna need it before this day is over.” To his adjutant, played by Eddie Albert, he says “Hell, no, we’re not leaving. We’re gonna get up that hill.” Most famously, to the men awaiting orders on the beach, he yells, “There are only two kinds of people on this beach: those that are dead and those that are gonna die. Now let’s get the hell out of here!”

Mitchum, with his sleepy-looking eyelids and laid-back manner, is not always the most exciting performer to watch. But as General Cota, Mitchum is at the top of his game. He’s vibrant, belligerent and alive, exhorting the operation to take place with one explosive word, “Go!” and chomping an always-present cigar with gusto, aching to get going and finish the brutal but necessary job at hand. Mitchum is absolutely inspirational in an inspirational role and leads by example. It is among his finest portrayals, even if it is brief in terms of screen time.

George C. Scott

as General

Buck Turgidson,

U.S. Air Force

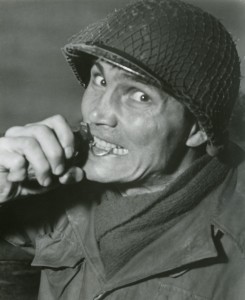

While Peter Sellers received all of the attention (and a well-deserved Oscar nomination) for Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb in 1964, it is George C. Scott who runs away with the picture. In a movie full of nuttiness there is no one nuttier than Scott’s Air Force General “Buck” Turgidson.

Although Scott was reportedly annoyed that director Stanley Kubrick kept pushing him into greater degrees of farce, even Scott realized that the director knew what he was doing, and appreciated the film. Turgidson is a caricature of studly masculinity, ready to duke it out with the Russkies but preferring to go back home to the charms of his loyal secretary (who is, by the way, also the centerfold model in the Playboy magazine on board the bomber headed toward Moscow).

Turgidson is definitely a hawk, jealously guarding our national secrets even at the expense of the fate of the world. He characterizes the decision of General Ripper (Sterling Hayden) to send a fleet of B-52 bombers to obliterate Moscow as the general “exceeding his authority,” yet he doesn’t entirely disagree with Ripper’s thinking. He advises the president to seriously consider following Ripper’s lead and finish the job, saving the world from Commie control.

Scott is as animated in the role as an actor can be. His face seems to be made of rubber, particularly in the War Room sequence, trying to explain Ripper’s actions and their probable consequences to America. And after Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers) broaches the notion of underground living with a female to male ratio of 10 to 1, Scott’s demeanor is almost orgasmic.

It is in the War Room sequence that Scott really shines. Before, General Turgidson was merely relaying information and probabilities to the Joint Chiefs and the president. In the War Room, the general begins espousing his true feelings about the situation, the positive aspects of a nuclear skirmish and the need to always stay ahead of the Russians. He gleefully describes the beauty of the B-52 barreling over the Russian countryside under radar level, mindless of the fact that the bomber holds the world’s fate in its bomb bay. And it is Scott who has the last important dialogue, an ironic phrase that echoes the central conundrum of the entire Cold War. “Mr. President, we cannot allow a mineshaft gap!”

Comic performances rarely seem to garner the critical recognition that they often deserve, and in this movie Peter Sellers hogged all the attention with his three roles. Sellers was also supposed to play the bomber pilot, but his problems with a Texas accent and a broken ankle landed Slim Pickens the role. As good as Sellers is, however, Scott is just as good and a case can be made that Sterling Hayden is also on that exalted level. George C. Scott should have been recognized for this roguish, wicked achievement.

Karl Malden

as General

Omar Bradley,

U.S. Army

George C. Scott won (and infamously refused) an Oscar for his title role in 1970’s Patton, yet the film boasts yet another terrific performance, that of Karl Malden as General Omar Bradley.

Bradley recommended Patton for the command of the II Corps in Africa and Eisenhower installed the maverick general. Patton wanted Bradley as his deputy, and Bradley complied. They spent the next two years both together and apart, commanding Allied armies through the march across France into Germany. Patton was the emotional leader, apoplectic when his men wouldn’t fight as hard as he but supportive of those he felt worthy of respect. Bradley was analytical and calm, weighing each situation with care and reaching for the strategic solution. They complemented each other like no two generals (and allied rivals) before or since.

Much of the action and character development in Patton is viewed from Bradley’s perspective. As his initial benefactor and then battle companion, Bradley was in a position to note all the nuances and oddities of Patton in detail. Furthermore, Bradley’s “normalcy” balances the picture, allowing Patton’s eccentricities and glory in battle to stand alone, observed from a meaningful, subjective distance.

Karl Malden steps up to the role with a strength as innate and powerful as Scott’s, although it is kept in check while Scott’s is let loose to prowl and hector. Malden’s Bradley could be bull-headed as well, but he seems positively serene when placed next to Scott’s Patton. Malden infuses his acting with considered thoughtfulness, tiny moments when we can see him thinking about the ramifications of the decisions Bradley must make. Scott, on the other hand, reacts instantaneously with the sure assurance of his own righteousness. That difference is what makes them so interesting.

Malden is marvelous as Bradley, trying to keep his rambunctious ally in check one moment, then trying to keep up with him the next. Malden conveys Bradley’s consternation well but never allows his general, who outranks Patton, to lose his temper. That in itself transmits much about both men and provides viewers with a solid vantage point to observe and judge their characters. To its credit, Patton can be seen as one of cinema’s great, epic character studies.

Lee Marvin

as The Sergeant,

U.S. Army

Writer-director Sam Fuller spent two decades trying to get his World War II adventure The Big Red One produced. He finally succeeded and in 1980 his film was released, though it was considerably shortened from its original length. It is now available on DVD in both its original and reconstructed forms.

The film follows an unnamed sergeant (Lee Marvin) and four young recruits through three long, harrowing years of duty from the Kasserine Pass in Africa to the shores of Sicily, from an asylum in Belgium to a concentration camp in Germany. Along the way the recruits lose their innocence and gain a terrible understanding of men at their worst — and their best. Battle hardens all of them but to their credit they never lose their basic humanity.

The sergeant is the squad’s father figure, although he refuses to baby them in any way. He is gruff and hard but that is for their own good. They gradually realize that he is keeping them alive, and they begin to absorb his wisdom and act as he does to survive. As they pass from one battlefront to another the “Four Horsemen,” as they come to be called, form a solid, self-sufficient unit, well-oiled by the blood and tears they have shed under chaotic conditions.

Originally, Fuller sought John Wayne for his sergeant but the years passed before that arrangement could be finalized. Wayne died in 1979, as The Big Red One was finally put before the cameras. Lee Marvin was cast just after his famous palimony trial, as he was trying to resurrect his career. His tough demeanor is perfect for the role; Marvin had fought in the South Pacific and been injured at Saipan, spending months in a hospital after being shot in the backside, one of the only men to survive from his platoon. In fact, the scene in which the sergeant is wounded in Africa is staged in much the same manner as Marvin’s actual injury.

While the sergeant is unnamed, it is difficult to think of another actor who could bring the gravitas and intrinsic fortitude to the role that Marvin does. Having actually experienced the war and its adrenaline-fueled insanity, he lives the material with a verisimilitude that cannot be questioned. And it isn’t all rah-rah patriotism. Fuller’s movie isn’t about the glory of righteousness, it’s about the very human feelings of people exposed to its brutality and carnage.

Marvin is certainly explosive in certain scenes. He’s deadly cold when urging reluctant Private Griff (Mark Hamill) forward with the Bangalore Relay on Omaha Beach. He’s absolutely wild in the tank scene when a French woman is having a baby. And he is at his absolute best in the concentration camp scene, lifting a frail little boy onto his shoulders for a brief, poignant ride outside in the fresh air, silent as the boy dies, but continuing to walk around with the weight of the world upon his broad shoulders.

Clint Eastwood

as Gunnery Sergeant

Thomas Highway,

U.S. Marine Corps

To date the only Hollywood chronicle of the 1983 American invasion of Grenada, Heartbreak Ridge (1986) is a Clint Eastwood movie with a masterful leading performance by… Clint Eastwood.

Eastwood plays Marine Gunnery Sergeant Thomas Highway, a veteran of Korea and Vietnam whose current life revolves around training the new Marine Corps recruits. Highway is, like all training personnel, one tough and demanding instructor. He leads his male and female charges through every torture imaginable as they begin to accept military discipline and push their bodies harder than ever before. Highway does have a personal life, but it’s a weird one; he’s trying to win back his ex-wife (Marsha Mason), the only woman who has ever made him happy. To do so he humiliates himself endlessly (and entertainingly).

Eastwood uses his voice as never before. He’s as fit as ever and tougher than any of the younger actors who test his character’s will. With Mason, Eastwood tries to be gentle, and the battle going on within him between bending to her will and following his normal instincts is hugely satisfying to watch. Eastwood allows the comedy to play naturally and because the comedy erupts from fairly dramatic situations, it works far more effectively than just clowning around (which is what defines so much comedy today).

Yet this is a fully fleshed achievement for Eastwood. Tom Highway is a man with sure beliefs, resounding good sense and the will to triumph in any physical situation. He’s less sure around his ex-wife, but he deserves all the credit in the world for trying to adjust to her needs. When the call to action comes, Eastwood hardens himself further and leads his charges into battle with honor and trust.

Any historian will note that Grenada was invaded by the U.S. Army, not the Marine Corps. Eastwood tried to get Army cooperation, but was rebuffed, as the Department of Defense didn’t like the script. Instead, the Marine Corps was used, although their high-level commanders didn’t appreciate the script either. Either way, any armed force led by the inimitable Clint Eastwood at the height of his acting prowess is guaranteed victory.

R. Lee Ermey

as Gunnery

Sergeant Hartman,

U.S. Marine Corps

No actor, including the aforementioned Clint Eastwood, has ever, ever portrayed a drill sergeant as capably or convincingly as R. Lee Ermey does in Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam War film Full Metal Jacket (1987). Like Jack Palance, the man is a force of nature.

Ermey had previously played drill instructors or gunnery sergeants in The Boys in Company C (1978) and Purple Hearts (1984), plus a helicopter pilot in Apocalypse Now (1979) but it was his hiring as a technical advisor for Full Metal Jacket that changed his career. Kubrick was so impressed by Ermey and his instant authority that he bypassed his original choice (Bill McKinney) and hired Ermey to portray Sgt. Hartman.

Having spent eleven years in the Marine Corps, Ermey was well-suited to play a gunnery sergeant; in fact, he was awarded the honorary rank of Gunnery Sergeant of the Marine Corps following his retirement from the service. In the movie, he acts just like he lived (which may be why he was overlooked by Oscar voters). He constantly berates his recruits until they jump at his command; he breaks their spirits so he can instill the ways of the Marine Corps. He does exactly what he has been trained to do.

Sgt. Hartman’s methods are put under a microscope in this movie and the fate of the sergeant is directed by his attitude toward one particular recruit. Kubrick’s point is that perhaps the madness of war begins before the men actually go to war; it begins in the preparation. Ermey stands tall as the personification of that preparation and it is up to the viewer to determine how to respond.

Denzel Washington

as Lieutenant Colonel

Nat Serling,

U.S. Army

When Courage Under Fire was released in 1996 I was astonished that Denzel Washington failed to be nominated for an Oscar. It’s a terrific movie and he is absolutely great in it as an Army officer shelved after a “friendly fire” incident in the Gulf War. His new assignment is to determine if a female pilot killed in action in the same conflict should receive the Congresssional Medal of Honor.

The movie alternates between Lt. Col. Serling’s nightmares of battle, in which he accidentally fired on an American tank, killing his best friend, and his active investigation into the death of pilot Captain Karen Walden (Meg Ryan). The film uses a Roshomon-style framework as each witness that Serling questions has a completely different perspective on Walden’s abilities and ultimate fate. Eventually both cases are thoroughly explained and put to rest.

Cast against type, Meg Ryan is good, but sometimes not particularly believable as the abrasive pilot who has more trouble with her colleagues than with the enemy. (This is because her character is always seen through the eyes of others, and nobody sees her in the same way). Matt Damon shines in a small role and I liked Lou Diamond Phillips a lot, too. Denzel Washington is magnificent in an emotionally taxing role. Serling suffers the guilt of the damned, yet he must still find a way to function and provide Captain Walden’s case the attention it deserves, a task made more delicate by the pressure put on him by Army brass who want to award a Medal of Honor to a woman for the first time to fuel public sentiment.

Washington has never been better than the scene late in the movie where he reluctantly visits the parents of the friend he killed and tells them what really happened. The weight on his conscience is palpable throughout the drama, yet unburdening himself only deepens it, at least for a time. But you get the feeling that Serling will, somehow, get past the guilt, and that he should. It’s a masterful piece of acting, one of the finest in the ‘90s.

These ten performances were superb, but evidently not good enough to be recognized by Oscar voters. There are various reasons why, usually owing to indomitable competition. Eight of the ten actors had been nominated before these movies were seen, which could also be a factor against them. One was nominated afterward (Clint Eastwood), while R. Lee Ermey has never been recognized by the Academy. But all of these roles share the common bond of excellent quality, of being outstanding dramatic (and comic) work.

The war film continues to be a popular genre, as releases continue throughout the years. There are few situations as dramatic as war and history is full of stories, both epic and personal, waiting to be told.

These ten excellent performances illuminate what can be done by gifted actors and filmmakers. It’s true that my choices are all officers, perhaps because officers bear responsibility and that challenges the actors more.

Nevertheless, these and other movies provide actors with choice parts and viewers with quality drama that is not only entertaining, but filled with important things to say about war and its terrible destruction. ✥