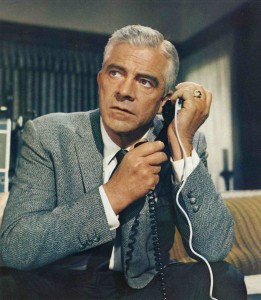

Dana Andrews (1909-1992), was a handsome, versatile actor with a wonderfully smooth voice best known for some classic 1940s dramas, and who, between 1957 and 1975, came to embody some of the unluckiest pilots in the movies. Those few appearances are quite memorable, at least to people like me who enjoy aviation dramas. Andrews was not a pilot in real life, but he occasionally played one on the big screen.

Early in his career, Andrews played pilots in The Purple Heart and Wing and a Prayer (both 1944) and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). These war films present Andrews as a fine pilot and squadron leader — although his plane (one of Doolittle’s raiders) is downed and the crew captured in The Purple Heart. Still, nothing in this trio of titles suggests that Andrews could or would be unfortunate or unlucky in the cinematic skies of the future. However, that would change in 1957, when Andrews accepted the lead role in Zero Hour!

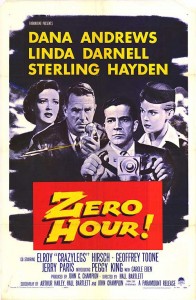

Andrews portrays a troubled World War II pilot named Ted Stryker (yes, that Ted Stryker) who has not been able to keep a steady job since the war. He finally gets a new job and returns home to tell his wife, only to find that she (Linda Darnell) is flying out of town for good. Desperate to keep his marriage alive, he quickly buys a ticket and joins his wife and son on the flight from Calgary to Vancouver. Thankfully for everyone on board, he eats the meat. Both pilots have the fish, as do several of the passengers, including Stryker’s son Joey (Raymond Ferrell). All of them fall desperately ill, and it falls to the former pilot Stryker to get them safely back down. The only problem is that Stryker is a pilot without any confidence. He flew fighter planes, not big commercial jets, and his last mission in the war resulted in six of his men diving their planes into the ground — a moment which is revisited several times during the film.

Andrews portrays a troubled World War II pilot named Ted Stryker (yes, that Ted Stryker) who has not been able to keep a steady job since the war. He finally gets a new job and returns home to tell his wife, only to find that she (Linda Darnell) is flying out of town for good. Desperate to keep his marriage alive, he quickly buys a ticket and joins his wife and son on the flight from Calgary to Vancouver. Thankfully for everyone on board, he eats the meat. Both pilots have the fish, as do several of the passengers, including Stryker’s son Joey (Raymond Ferrell). All of them fall desperately ill, and it falls to the former pilot Stryker to get them safely back down. The only problem is that Stryker is a pilot without any confidence. He flew fighter planes, not big commercial jets, and his last mission in the war resulted in six of his men diving their planes into the ground — a moment which is revisited several times during the film.

In order to talk Stryker down safely the airline brings in hotheaded pilot Captain Martin Treleaven (Sterling Hayden), who knew Stryker during the war, and is fairly certain that he is incapable of bringing the jet safely down to Earth. But Treleaven gives Stryker all the help he can and Vancouver braces for impact. The landing is very rough, and the aircraft eventually loses its wheels (twice, if you watch very carefully), finally fishtailing to a halt on the foggy concrete. Yes, Stryker does bring the plane in, but it isn’t a ride anyone would have wanted to take by choice.

In order to talk Stryker down safely the airline brings in hotheaded pilot Captain Martin Treleaven (Sterling Hayden), who knew Stryker during the war, and is fairly certain that he is incapable of bringing the jet safely down to Earth. But Treleaven gives Stryker all the help he can and Vancouver braces for impact. The landing is very rough, and the aircraft eventually loses its wheels (twice, if you watch very carefully), finally fishtailing to a halt on the foggy concrete. Yes, Stryker does bring the plane in, but it isn’t a ride anyone would have wanted to take by choice.

Arthur Hailey wrote the original story for Zero Hour! more than a decade before he wrote the bestselling Airport. In fact, he had written the story for Canadian television and it had appeared in 1956 as Flight Into Danger, with James Doohan (Star Trek‘s Scotty) as the reluctant pilot hero, then known as George Spencer. For Zero Hour! a new name was chosen. When the story was again told in 1971, as the TV movie Terror in the Sky, with Doug McClure, the pilot’s name once again reverted to George Spencer. So Arthur Hailey saw this story produced not once, not twice, but three separate times within fifteen years.

Hall Bartlett directs Zero Hour! with urgency and more than a few unintentionally funny moments, but it is not for me the camp classic that it is now advertised as by Warner Bros. Back in 1957, it was taken very seriously, with the tagline “It builds to the tensest 50 minutes in the history of the screen!” But in 1980, after the wave of Airport flybys had become progressively more ridiculous, Arthur Hailey’s story was recycled once again, this time with as many gags, puns, non sequiturs and deadpan readings of crazy dialogue as could be imagined. The film was Airplane! and it uses the structure of Zero Hour! as its framework. Ted Stryker (Robert Hays) is even more hapless and haunted by guilt, but like Dana Andrews, he brings the ship home (albeit with a very bumpy ride).

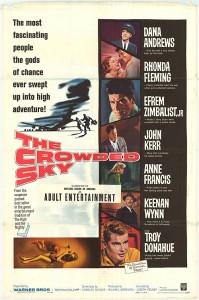

Andrews was faced with another crisis in The Crowded Sky (1960), an aviation drama that results in a mid-air collision. Based on a novel by Hank Searls, this aerial melodrama is directed by Joseph Pevney. This time Andrews is cocky airline pilot Dick Barnett, who has flown seven million miles in the air, and is now guiding a DC-6 from Washington D.C. to Los Angeles. On the other side of America, Navy pilot Dale Heath (Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.) has taken off heading east. Somewhere over Texas they meet, because of the Navy jet’s bad radio and Barnett’s penchant for flying above his appropriate altitude to avoid turbulence.

Andrews was faced with another crisis in The Crowded Sky (1960), an aviation drama that results in a mid-air collision. Based on a novel by Hank Searls, this aerial melodrama is directed by Joseph Pevney. This time Andrews is cocky airline pilot Dick Barnett, who has flown seven million miles in the air, and is now guiding a DC-6 from Washington D.C. to Los Angeles. On the other side of America, Navy pilot Dale Heath (Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.) has taken off heading east. Somewhere over Texas they meet, because of the Navy jet’s bad radio and Barnett’s penchant for flying above his appropriate altitude to avoid turbulence.

The Crowded Sky, much like The High and the Mighty before it, focuses as much on the personal lives of its crew and passengers, seen in flashbacks, as on its current situation. In particular, the rocky marriage of Heath to a beautiful redheaded tramp (Rhonda Fleming) and the odd courtship between airline copilot Mike Rule (John Kerr, who seems far too young to be an experienced copilot) and stewardess (and self-proclaimed former tramp) Kitty Foster (Anne Francis) comprise much of the film’s running time. Barnett has a teenage son (Ken Currie) with whom he has trouble relating, but that seems the least of his problems, as his relationship with his copilot is strained and often seems headed toward violence.

Pilot Barnett is in control here, flying above his stated altitude because it is less bumpy for the “geese” in the passenger cabin. His intentions are good, of course, but the film states in unequivocal terms that altitude orders are established for everyone’s safety, and he is compromising it. Ultimately, it is Dale Heath who goes against his own survival instincts and dives beneath the jet, bringing a quick end to his trip but potentially saving the lives of the airliner’s passengers. Barnett and Rule bring down the jet quickly and safely, although it somehow misses the foam laid on the runway for the missing nose gear. Later, Barnett accepts the blame for flying at the incorrect altitude, and by admitting his mistake (proving that he, too, can be foolish), finally bonds with his son.

The moments before impact are very impressive, as the aircraft are seen as missiles flying directly at each other. The impact itself is not so impressive, done by models in an obvious fashion. Much of the personal drama is vintage soap opera, especially the strange reunion between a writer (Keenan Wynn) and a former flame he does not recognize (Jean Willes). Another odd couple is a young actor (Tom Gilson) who cannot relate to his next role and his motherly agent (Patsy Kelly), who rolls her eyes at his foolishness at every opportunity. The film’s dialogue is awfully corny, and poor Troy Donahue has incredibly little to do as Heath’s wary passenger. Yet it does deliver some of what it promises, and the quick descent after the collision is appropriately harrowing. Barnett handles the situation calmly, piloting the disabled plane — including one engine which is on fire and threatening to explode or fall off — with professional aplomb. But again, it isn’t a ride anyone would choose to take. Andrews’ reputation as a good but unlucky pilot was almost complete.

The moments before impact are very impressive, as the aircraft are seen as missiles flying directly at each other. The impact itself is not so impressive, done by models in an obvious fashion. Much of the personal drama is vintage soap opera, especially the strange reunion between a writer (Keenan Wynn) and a former flame he does not recognize (Jean Willes). Another odd couple is a young actor (Tom Gilson) who cannot relate to his next role and his motherly agent (Patsy Kelly), who rolls her eyes at his foolishness at every opportunity. The film’s dialogue is awfully corny, and poor Troy Donahue has incredibly little to do as Heath’s wary passenger. Yet it does deliver some of what it promises, and the quick descent after the collision is appropriately harrowing. Barnett handles the situation calmly, piloting the disabled plane — including one engine which is on fire and threatening to explode or fall off — with professional aplomb. But again, it isn’t a ride anyone would choose to take. Andrews’ reputation as a good but unlucky pilot was almost complete.

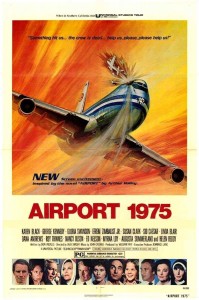

Ironically, Dana Andrews and Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. would dramatically converge in the air one more time, in the all-star aviation drama Airport ’75 (1974), the first sequel to Airport. Arthur Hailey had nothing to do with this project, other than to license the Airport title to Universal, which was determined to reap even greater profits from its 1970 hit (and which is generally credited to jump-starting the disaster movie cycle of the 1970s). The only recurring character from the original tale is Joe Patroni (George Kennedy), the Chicago airport maintenance chief who, in Airport ’75, is now Vice President of Operations for fictional Columbia Airlines in Los Angeles. Unfortunately for him, his wife (Susan Clark) and son (Brian Morrison) are flying the fateful 747 westbound to meet him there.

Ironically, Dana Andrews and Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. would dramatically converge in the air one more time, in the all-star aviation drama Airport ’75 (1974), the first sequel to Airport. Arthur Hailey had nothing to do with this project, other than to license the Airport title to Universal, which was determined to reap even greater profits from its 1970 hit (and which is generally credited to jump-starting the disaster movie cycle of the 1970s). The only recurring character from the original tale is Joe Patroni (George Kennedy), the Chicago airport maintenance chief who, in Airport ’75, is now Vice President of Operations for fictional Columbia Airlines in Los Angeles. Unfortunately for him, his wife (Susan Clark) and son (Brian Morrison) are flying the fateful 747 westbound to meet him there.

The path of the commercial jet is the same as in The Crowded Sky, from Washington D.C. to Los Angeles. However, heavy fog over California dictates a detour to Salt Lake City. But this time around it is Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. piloting the jet as Captain Stacy, and Dana Andrews as regional salesman Scott Freeman, flying the small plane, a Beechcraft Baron. Freeman’s plane takes off from New Mexico, heading for Boise, Idaho, but Boise is also fogged in, and he is also diverted to Salt Lake City. The collision occurs over Utah when Freeman suddenly has a heart attack and loses control, swerving the plane into the path of the airliner. This is curious because according to the air traffic controller, his Baron is said to be second in line to approach the Salt Lake City airport, behind the 747. Unless they are in a circling pattern, there should be no way for him to get in front of the bigger, faster jet.

The moment just before the impact, pictured above, is unfortunate, mainly because it lasts too long. It seems for a beat or two that the plane is hovering right in front of the 747 cockpit, not moving forward at all, so that Captain Stacy and Copilot Urias (Roy Thinnes) can react to its sudden presence — even though they have been warned to watch for it. It is a moment that deserves a better process shot than the studio could provide. That moment is also Dana Andrews’ swan song as a cinematic pilot, although Scott Freeman was probably dead before his Baron glanced off the 747 fuselage. The actual Beechcraft Baron used in the movie had an eerily ignominious end in 1989, when it was involved in a real mid-air collision, in which both pilots were killed.

The moment just before the impact, pictured above, is unfortunate, mainly because it lasts too long. It seems for a beat or two that the plane is hovering right in front of the 747 cockpit, not moving forward at all, so that Captain Stacy and Copilot Urias (Roy Thinnes) can react to its sudden presence — even though they have been warned to watch for it. It is a moment that deserves a better process shot than the studio could provide. That moment is also Dana Andrews’ swan song as a cinematic pilot, although Scott Freeman was probably dead before his Baron glanced off the 747 fuselage. The actual Beechcraft Baron used in the movie had an eerily ignominious end in 1989, when it was involved in a real mid-air collision, in which both pilots were killed.

The rest of the film features the frightened all-star cast (including Gloria Swanson as herself) and the heroics of Alan Murdock (Charlton Heston) being lowered through the cockpit hole by high-speed helicopter after Major John Alexander (Ed Nelson) dies in a previous attempt. It is up to Murdock to land the stricken airliner in Salt Lake City despite all the damage and he does so with typical Heston-like grim heroism. Charlton Heston had his own bad luck as a movie pilot — besides this movie, his 707 is hijacked in Skyjacked (1972) and his DC-10 blows a tail engine in the exceptional A Thousand Heroes (1992, TVM), a true story that replicates a 1989 crash in Sioux City, Iowa. And of course, that’s not even mentioning his captaining of a spacecraft that travels into the future and lands on the Planet of the Apes (1968). Still, Heston was an actor who often seemed larger than life, and able to handle anything fate could throw at him. That is not the case with Dana Andrews.

Dana Andrews’ chief asset as an actor (beside that velvety voice) was his commonality, for lack of a better term. He seemed like someone you could know, someone who might live down the street. Writer James McKay describes Andrews’s appeal in his book Dana Andrews: The Face of Noir (2010): “… His acting style subtly projected a decent all-American guy, whose outlook was tested and tempered by a susceptibility to disappointment, inner bitterness or moral dilemma. As a consequence, his characters were sometimes noted for their ambiguity and an air of restrained heroism — qualities that became a hallmark throughout much of his career.”

“Restrained heroism” certainly describes many of Andrews’ screen appearances, from his handling of the Zero Hour! DC-6 to the intriguing Cold War espionage thriller The Fearmakers (1958). His forty-five year movie career boasts genuine classics like The Westerner (1940), Ball of Fire (1941), The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), Laura (1944), A Walk in the Sun (1945), The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), Boomerang! (1947) and Night of the Demon (1957), and a number of other lesser but still memorable titles, including two of my favorites from 1965: Crack in the World and The Satan Bug. He usually improved any project he was in, and his urbane manner always brought a welcome sense of propriety, culture and sophistication to his roles. Like James McKay I have always enjoyed Dana Andrews’ performances… but I sure wouldn’t want to be flying at the same time that one of his characters was in the air. No, sir. I would be taking the train. 24 May 2012.

I enjoyed the piece on Dana Andrews as pilot. Zero Hour! was a comeback for him. He had gone through a terrible time on Elephant Walk, filmed during his brother’s sudden death. Dana turned to drink and the producers of Zero Hour! were wary of using him. But he promised he would deliver a sober performance, and he did. I tell all about it in the first biography of Dana Andrews, titled HOLLYWOOD ENIGMA: DANA ANDREWS, which will be published by University Press of Mississippi in September. I had access to his diary, his letters, and many other documents as well as the full cooperation of his wonderful family.

Carl, I’m pleased you enjoyed the article. Dana Andrews is overdue for a good biography, and I look forward to reading it. I used James McKay’s book as a reference, which is more a commentary of Andrews’ career, much like my own books about Lee Marvin and Gloria Grahame, neither of which are standard biographies. McKay’s book is very worthwhile, with lots of background information.

There is one more connection that Filmbobbery has to Dana Andrews. Back in 2005 (7:1) I and two of my subscribers wrote an article on Academy Award omissions, picking five actors each who had never been nominated for performance Oscars. The first actor chosen by Richard Thompson, the man who led off the article, was Dana Andrews. His alcoholism aside, there is no question that Andrews was a fine actor who appeared in several great movies, and that he remains grossly under-appreciated today.

Just saw your comment. There is a passage in my biography, HOLLYWOOD ENIGMA: DANA ANDREWS, in which a prominent film critic writes to Dana saying he deserves an Academy Award but probably will never get one. Why? Because of Dana’s underplayiing. The Academy went for flashier performances.