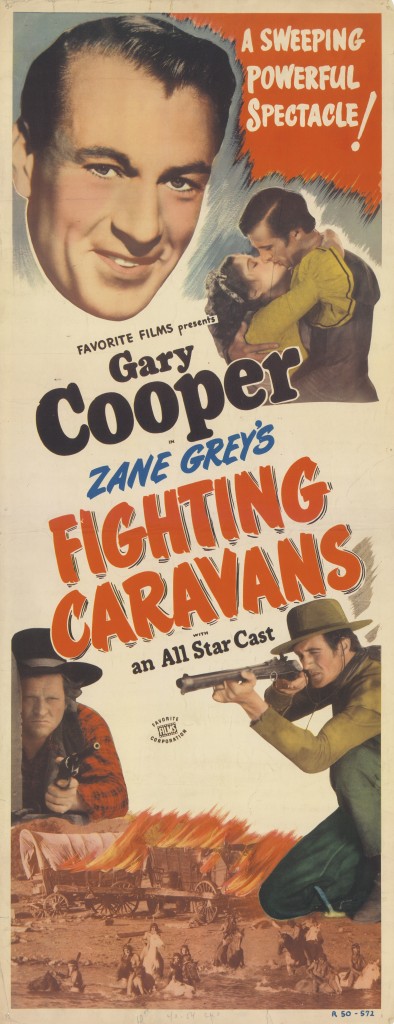

Our fourth potential classic of 2015 is one of the more than one hundred film adaptations of the works of popular western author Zane Grey. Fighting Caravans (1931) is a wagon train story of pioneers crossing the West from Missouri to California, beset by bad weather, Indian attacks, and, of course, the desolation of the land itself. Grey’s novel was published in 1929, with the movie version coming just two years later, a relatively quick adaptation. Grey’s book would be used again just three years later, in 1934 — by the same studio, Paramount Pictures — for a movie titled Wagon Wheels with Randolph Scott.

Our fourth potential classic of 2015 is one of the more than one hundred film adaptations of the works of popular western author Zane Grey. Fighting Caravans (1931) is a wagon train story of pioneers crossing the West from Missouri to California, beset by bad weather, Indian attacks, and, of course, the desolation of the land itself. Grey’s novel was published in 1929, with the movie version coming just two years later, a relatively quick adaptation. Grey’s book would be used again just three years later, in 1934 — by the same studio, Paramount Pictures — for a movie titled Wagon Wheels with Randolph Scott.

Fighting Caravans was a major production for Paramount, with a budget approaching one million dollars (by comparison, the budget for Wagon Wheels was one fifth that amount). The studio was betting that interest in pioneer pictures was still strong, and with good reason. While the first major such film, The Covered Wagon (1923), which was also a Paramount product, had been made almost a decade earlier, other, more recent projects had maintained interest in the topic. Fox had invested some two million dollars in The Big Trail in 1930, a very similar film which starred a very young John Wayne; the film was not successful and Wayne would spend the 1930s in B-westerns until John Ford put him in Stagecoach. In 1931 RKO released Cimarron, which depicted the Oklahoma land rush and the settling of that new territory; Cimarron became the first western-themed movie to win the Best Picture Oscar. Plus, the name of Zane Grey was still remarkably popular. The author was publishing an average of two novels a year, most of which became best sellers, and most of which formed the basis for motion pictures. More than a few of Grey’s books were adapted three or more times!

In this movie a young scout, Clint Belmet (Gary Cooper), is needed to help lead a wagon train from Missouri to California. But the sheriff (Charles Winninger) of the Missouri town of Independence doesn’t want Belmet to leave. Two older scouts, Bill Jackson (Ernest Torrence) and Jim Bridger (Tully Marshall), intervene on Belmet’s behalf, telling the sheriff and the saloon crowd watching that Belmet has married a young woman and is on his honeymoon. A young woman, Felice (Lili Damita), steps forward, and Belmet goes along with the fable. The sheriff sets Belmet free, with his blessing, and the wagon train gets moving west. Belmet is thrilled at having to pretend to be married, but his thrills don’t last long — Felice soon sets everyone straight and Belmet is back on his own.

Belmet is one of three scouts hired to keep the wagon train moving and safe. Jackson and Bridger are much older and have taken Belmet under their protective wings to teach him about the West and mold him in their image. Bridger, of course, was an actual person, a legendary fur trapper, guide and scout with many western locales named for him. There was a real scout named Bill Jackson, but he was an Indian scout, half Pikuni and half Blackfoot. Why is Bridger was teamed with Bill Jackson, whom he may or may not have known, and why is Jackson portrayed as a white Southerner, serving as the movie’s comic relief? Lo and behold, Bill Jackson and Jim Bridger are characters in the earlier pioneer film, The Covered Wagon, and they are played by the same actors, Ernest Torrence and Tully Marshall! Evidently the Paramount brass felt the characters were integral to the success of The Covered Wagon and inserted them into this story — for neither man is in the Zane Grey book. Coincidentally, Ernest Torrence also appears in the 1924 Zane Grey adaptation Heritage of the Desert, while Tully Marshall also appears with John Wayne in The Big Trail.

The scouts are responsible for the wagon train’s security; they must choose the safest, smoothest path forward, yet also guard the rear. They must lead the convoy to water and provide food when necessary. They must recognize dangers, and changes in the wilderness that might affect the journey. To serve as a scout was an honor, but also a tremendous responsibility. The two older scouts seem almost too playful in their duties; thank goodness that the youthful, energetic Belmet is around as well. To be honest, I do not particularly care for Jackson; his incessant cornpone rambling grates on my nerves. Bridger is easier to take, yet he seems to be the second banana in this thin bunch. And a great deal of the movie is concerned with the scouts’ interactions. Too much so, to my way of thinking.

The wagon train heads west, with single woman Felice. She had been told by the scouts that only her cooperation with them to “rescue” Belmet would allow her to join the wagon train, but that is not true. The leader, Jim Couch (Roy Stewart), tells her quite plainly that anyone with a wagon is welcome. Felice was to accompany her father on the trip, but he died back in Ohio. Naturally Felice is angry with Belmet and the scouts for their duplicity, chasing them away, but they will be protective of her the rest of the trip anyway.

The obstacles on their way to California are weather, terrain and Indians. For some reason — perhaps because this was lensed in pretty Sonoma, California — bad or rough weather is rarely an issue. The terrain is tough, particularly as they prepare to cross the Rocky Mountains and a dangerous river. The plains Indians are the major danger, especially as the Indians seem to be following the train across the Rockies, which is very uncharacteristic of them. Could somebody be surreptitiously aiding the Indians, perhaps prodding them to follow and attack? This is a Zane Grey story, so of course such chicanery is more than a possibility.

A couple of sequences stand out — the crossing of the Rocky Mountains, and the river crossing, which climaxes with an Indian attack. The wagon train is at home on the plains but that is not the case in the mountains. Directors Otto Brower and David Burton stage the brief mountainous scenes skillfully, detailing the difficulties of moving the huge wagons with their five-foot tall wheels through deep snow and up and down treacherous slopes. If anything these scenes are too short, because these glimpses of backbreaking work and danger and bravery are what humanize scripts, creating empathy for the travelers undergoing such hardships and challenges.

Yet these scenes, which ought to be the meat and potatoes of the film, are strictly a side dish. Establishing shots depict the wagon train moving across the plains, through the snow and across the river but the details of the journey are eschewed in favor of the romantic complications and static dialogue scenes. Difficulties in filming are to blame — remember that this was 1930, the very dawn of the sound age, and that the cameras were huge and largely needed to be stationary — yet other films of the period were far more inventive and exciting in terms of their technical aspects. This film pales next to The Big Trail, for instance, which not only tells a similar story in far more compelling visual style, but does so while being lensed under even stricter parameters, using the 70 mm Fox Grandeur wide screen process. Yet another link to The Big Trail is that Gary Cooper was reportedly courted for its lead, and wanted it, but John Wayne was chosen instead. Cooper, of course, went on to make Fighting Caravans.

One of the oddest aspects, at least to me, is the lack of focus on the wagon train’s travelers. Of the dozens of people trekking across the plains we are introduced to no more than a handful of them. Only Felice is important to the story; Seth Higgins (Eugene Pallette) is an object of scorn and humor, while Lee Murdock (Fred Kohler) has a darker role to play. A couple of frontier women embody the pioneer spirit, choosing to go on in spite of the lack of an Army escort and other hardships, but that’s about it. The majority of the character action falls to Clint Belmet, his two scout friends and Felice to deliver. That’s just lazy writing.

It is also true that the story, and its emphasis on marriage as a romantic necessity, is very old fashioned. Mores have changed over time, so much so that viewers unaccustomed to vintage movies and their quaint customs may have difficulty either understanding or accepting why things are the way they are. This is the kind of thing that really “dates” movies, as much as fashion and modes of transportation. Things were different back then, and remember that this 1930 film is telling a story of the 1860s. Presenting Felice as a brave woman willing to endure the journey west alone was fairly brave for its time, although it seems inevitable that she would have to find a husband by the end of the trip.

Nor is there much of an historical perspective, which is a hallmark of Zane Grey’s writing. His stories not only entertain, but teach about the history and customs of the West — the way things used to be. But to include details about the prairie schooners, or the Indians who follow them, or the wildlife they encounter along the way takes time, and filmmakers are loathe to make the effort to explain things for fear of losing the audience’s attention. Action and dialogue are what work in film, so that is what is normally employed. The best filmmakers combine show and tell in entertaining fashion, but the best filmmakers didn’t make this movie. There are good reasons why people are not familiar with the work of Otto Brower and David Burton. Interestingly enough, Brower’s work as a director began with Zane Grey; six of his first nine films were Grey adaptations, of which Fighting Caravans was the last. This was the only Grey credit for David Burton.

And, sadly, the film has little except for the framework to do with Grey’s original story. This was often the case with Grey; screenwriters took his basic premise and a few of the character names, then often invented their own scenarios. The novel of Fighting Caravans introduces Clint Belmet as a twelve-year old, making the first of many trips back and forth the plains in 1856, almost a full decade before the time of this movie version. There is no Felice, or Jim Bridger, or Bill Jackson in the book. The novel, however, boasts Kit Carson as a character! In this case, like so many others, the book is better than the movie.

Is Fighting Caravans a classic? Sadly, no. While it was a major production at the time for Paramount Pictures the film lacks the grandeur that would have made it a bona fide classic. Fox’s similar adventure The Big Trail, directed by Raoul Walsh, dwarfs it in just about every important way. Fighting Caravans is dated, and dull, and uninspired. Far too much attention is paid to the two old scouts, especially early in the proceedings, and not nearly enough attention is given to the intrepid travelers. I am very interested in watching Wagon Wheels, the remake of just three years later, to see how it compares, as well as the silent film The Covered Wagon, which I have never seen. I was hoping that my first viewing of this film would be positive, but it really was not. Older films are sometimes tough going, but that isn’t my issue. Zane Grey’s source material is rewarding; Paramount Pictures and its odd teaming of two directors has failed to match it. ☆ ☆. 9 August 2015.