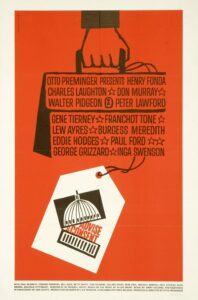

It’s been almost six years since our last Classic, but we are going to try again, beginning with this fascinating political drama from 1962, Advise and Consent. Based on the  Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Allen Drury — one of the best novels I have ever read — this all-star movie adaptation adroitly condenses Drury’s massive narrative about the controversy over a president’s choice for Secretary of State into a sharply focused study of the American body politic, at least as it existed back around 1960. Plenty of films, before and since, have tried to capture the elusive essence of political drama; this one is one of the finest, still timely and relevant sixty years after its initial release.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Allen Drury — one of the best novels I have ever read — this all-star movie adaptation adroitly condenses Drury’s massive narrative about the controversy over a president’s choice for Secretary of State into a sharply focused study of the American body politic, at least as it existed back around 1960. Plenty of films, before and since, have tried to capture the elusive essence of political drama; this one is one of the finest, still timely and relevant sixty years after its initial release.

The popular president (Franchot Tone) makes a controversial choice for Secretary of State, a former professor named Robert A. Leffingwell (Henry Fonda), a self-professed “egghead” whose rationalizations against war with the Soviets rankle the conservative side of the capital city. One senator in particular, Seeb Cooley of South Carolina (Charles Laughton, in his final film), has sworn to oppose the nominee, but his opposition is seen as a personal vendetta rather than a statement against Leffingwell’s or the president’s policies. Sides are quickly taken as the news spreads around Washington; the nomination is a surprise, because the president didn’t bother clearing it with anyone in his administration.

Political processes are rushed into effect, with the Senate Majority Leader, Bob Munson (Walter Pidgeon), and his Whip, Senator Stanley Danta (Paul Ford), quickly prodded into forming a sub-committee to examine and confirm or deny the nomination. Candidates to head the sub-committee are discussed but the task ultimately falls to one of the younger senators, Brigham (Brig) Anderson of Utah (Don Murray), an idealistic man whom the party leadership wants to promote into greater participation and prominence. One of the senators passed over for the assignment is Fred Van Ackerman of Wyoming (George Grizzard), an aggressive, humorless, mean-spirited sort who wholeheartedly supports the president’s choice and wants nothing to interfere with a quick confirmation.

Thus begins the political frenzy as sides are drawn, tactics are discussed and the senate begins its public discourse. More important are the behind-the-scenes arm twisting and pressure brought to bear so that the president gets his man confirmed, or, just as likely, that man is publicly humiliated once and for all. The film’s casting of Henry Fonda as the nominee for Secretary of State is brilliant because Fonda’s persona is one of honesty and integrity, putting most viewers on the president’s side very early in the process. However, as time moves on and we learn troublesome tidbits about Leffingwell’s past, our alliance with the character begins to shift. Interestingly, the film is not centered upon Leffingwell the character, nor even on the character of Leffingwell. It is truly an ensemble piece which swings in various directions to various protagonists as the drama unfolds. Leffingwell is important, certainly, and he gets his chance to shine in the senate sub-committee hearing, but then there are long stretches where he isn’t even present as the senators cope with the intrigue surrounding his nomination. This works even better in the book, a seven hundred-and-sixty (paperback) page tome where even minor characters fully explain their reasoning. The film, even at 139 minutes, only hints at some of Allen Drury’s meticulous plotting. By the way, Drury kept this particular political milieu going for five more novels, none of which, to my knowledge, have ever been subject to film adaptation. I’ve read the first two books and own the others, and look forward to sitting down with the next one every few years.

As should be expected, the film depicts the American political process in exacting detail, with as much authenticity and veracity as can be mustered. The senate train is seen in action; procedures are explained; tour guides narrate senate history and chamber rules; decorum is followed with painstakingly formal dialogue. Even though it is America circa 1960 it seems almost like another country compared to the garrulousness of our present era. Perhaps the senate still sounds this way; I’ll have to check out C-SPAN some day to see for sure.

But this is also an Otto Preminger film. Otto Preminger was famous worldwide as an extremely talented director, but also one who courted controversy in many of his films. They “pushed the envelope,” as the saying goes. Frankness and candor about sexual matters was usually the central issue, but Preminger’s films dealt bluntly with drug abuse, suicide, prostitution and even language in more adult manner than other directors. Advise and Consent is controversial for two reasons: one is a plot element built into the story, while the other involves the reception of the film. Drury’s novel addresses Senator Brigham Anderson’s tryst while stationed as a soldier in Hawaii, but without ever spelling out the nature of that tryst overtly. It was with another soldier. When certain people become aware of that tryst, and a letter that proves it, Brig Anderson is subjected to blackmail and more pressure than he can bear, with tragic results. Preminger not only makes that tryst crystal clear (without ever mentioning homosexuality; standards of the era would not permit it), but became the first mainstream filmmaker to stage a scene in a gay club, where Brig goes to confront his war buddy. It is the one element of the story which badly dates the drama, but we should remember and understand how daring it was in 1962.

The second controversy involves how some politicians and critics reacted to the film. Preminger was proud that the film affirmed the democratic process and that Washington insiders had helped secure hard-to-get city locations (but alas, not the senate chamber itself, which was replicated on a Hollywood soundstage). But some pols and critics felt that the drama held America up to international ridicule; that it showed how the political process could be undermined by sexual deviancy and rantings of that sort. One actual senator sponsored a bill to ensure the film would not find a release outside the United States (the bill was rebuffed). Even though Preminger and writer Wendell Mayes had changed Drury’s original ending to one a bit more compromised (and much more ironic), a fair number of politicians were riled that any major motion picture examined how they went about their work, let alone one which contained sexual prurience, blackmail and suicide. It seems silly and overblown now, but things have changed mightily in sixty years.

I think that Otto Preminger’s feeling about the film stands the test of time. It does affirm the political process, demonstrating how people at complete odds with each other can argue their perspectives, yet still get past those differences to get on with the nation’s work and remain friendly with one another no matter the outcome. It spotlights how dirty the pot can become (just think about what the president does to ensure his pick is pushed forward no matter what) yet it celebrates how the process itself determines the true outcome. Preminger commented often that viewers in other countries often told him how surprising it was to them that such a film could be made with governmental access and approval, which would not have been the case in their home lands. Like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, this movie takes a deep dive into America’s political realm and finds not only a cesspool of bribery and corruption but regular people trying to make the system work (sometimes for themselves, more often for their party, occasionally for the nation). It is, like America’s imperfect system, the most ideal compromise that could be constructed.

Is Advise and Consent a classic? Unquestionably. So many political films date themselves because they reflect the tenor of the times, and times change quickly. Situational dramas date more quickly, turning into historical period pieces that must be viewed through the context of the era. That is somewhat true of this drama, but the prickly points of policy are glossed over in favor of personality; Preminger’s film treats politics as theater of personality, which now seems prescient. By focusing on the people rather than the dilemma and the outcome he has created (adapted, really) a personal drama that seriously reflects the culture at the time but which sustains its universal appeal as personal drama first and foremost. The ending merely amplifies the irony of the situation and begins the procedure all over again. I personally think the film is brilliant, though not as thorough or deep as Drury’s novel. It remains one of the finest political stories ever put to film. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 19 March 2022.